The last time the world saw a tariff and trade war it was 2017, in Trump’s first term as President of the US when he took on the world’s second largest economy, China, in a tariff war. It ended with China too imposing retaliatory tariff increases on American imports and before we knew it, Europe and the entire world was being dragged into an unnecessary tariff and trade war that slowed global trade and economic growth.

The reasoning then was that China had stolen American jobs and investment, and that America was losing out with one of the largest trade deficits with the Middle Kingdom. It was also a way to bring back American companies’ investment home and with corporate tax cuts, the belief then was that this would revive investment and jobs in the US. Did it work? Well, investment in America did improve, but I am not sure how much of it was in creating greenfield and brownfield capacity and boosting employment, especially of the kind that was believed to have lost out to China. Most growth in investment must have come through the capital markets, where US has anyway been the leading FDI investment destination for decades.

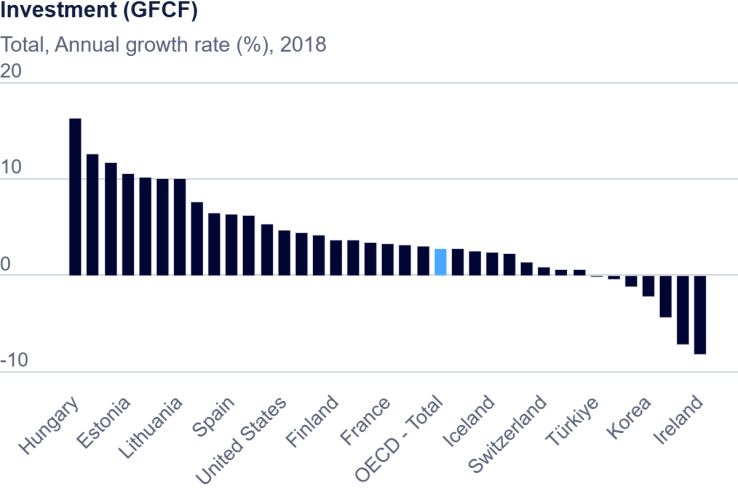

According to the OECD which has data on GFCF (gross fixed capital formation), capital investment in the US grew by 4.65% in 2018, slumped by half in 2019 to 2.63%, then declined by -1.23% in 2020 before reviving to 5.72% growth in 2021, as you can see in the OECD charts below. Besides, it is possible that a considerable part of this GFCF growth in the US is in the real estate sector, rather than in new manufacturing capacity. The fact is that the tariff hikes increased prices of most goods in America, American farmers suffered because China didn’t buy their produce, and Trump had to step in with a massive bailout package for them. Did it help American workers and consumers? This article from Brookings shares the impact of Trump’s trade war with China during his first term.

The truth I think is that Trump is obsessed with trade deficits, as I have written before on my blog. The facts also are that many American, Chinese and Taiwanese companies relocated to new manufacturing destinations in order to continue to enjoy lower labour cost arbitrage and work around the increased tariffs on China. It appears that Vietnam and Mexico were the main beneficiaries of that round of tariff hikes in Trump’s first term, with other countries such as Thailand, Laos and Cambodia also benefiting. It might be important to note that the US had the fourth largest trade deficit in 2023, with Vietnam to the tune of US$ 104.6 billion. India lost out in that round, even though there was much talk of the China+1 strategy at the time. Nevertheless, the US trade deficit with India in 2023 was US$ 43.7 billion. What are the chances that we might benefit this time around?

I think I will avoid looking at the whole tariff and trade issue as who wins and who loses, because as I have written before, nobody actually gains from a bruising and long trade war of this kind. Besides, this time if Trump goes ahead with his plan the tariff hikes are on all countries and all goods that the US imports, at the rate of 10%. China has been singled out for particularly harsh punishment with a 60% tariff hike on all imported merchandise from the country. The question for us to ponder is what will the impact of this be on global trade, on economies that trade with the US, on inflation both in America and around the world since many countries would respond with retaliatory tariff increases and the like. The other big question for us to think about is what would happen to global economic cooperation, trade and investment ties and international relations between countries.

As far as economic impact of these Trump 2.0 tariff increases is concerned, we must consider it from the point of view of whether the country is exporting commodities, intermediate goods that are required for the manufacture of finished products or completely finished goods to the US. In each of these cases, the economic impact would vary and countries must plan for how to respond to each of them.

I haven’t looked at US trade data in detail, but it seems to me from looking at the WITS (World Integrated Trade Solution) from the World Bank, that most countries exporting commodities (raw materials) to the US would not be that adversely affected by the tariff hikes. These commodities would mostly come from Canada, Latin America, Africa, China, Middle-East and South Asia. Tariff increases of commodities would of course increase the cost of manufacturing in the US, and depending on how much American domestic manufacturers can absorb and how much they need to pass on as price hikes to customers remains to be seen. It is also unlikely that all of the countries that export commodities to the US will respond with retaliatory tariff increases; if the value of their exports to the US is not too high, and if their exports are diversified across other markets and they can find new markets, they might not be compelled to respond with tariff hikes of their own.

The US does import commodities such as steel and aluminum and perhaps some critical minerals from China, but since Chinese imports will attract 60% tariff increases, China will have to be dealt with separately.

Countries that export intermediate goods that are either commodities or semi-finished goods, components, parts and the like are likely to be impacted quite significantly. This would be especially exacerbated, where the exported merchandise is part of a global supply chain as it could lead to all kinds of complications and disrupt global supply chains for many companies, industries and countries around the world. This certainly needs to be addressed with a plan at all levels – company, industry and country/region. WITS data on intermediate goods imported by the US suggests significant exposure to many countries, including India, and we ought to devise a careful response and mitigation measure.

Countries that export finished goods to the US are also likely to not be affected very much, if they enjoy a competitive advantage in the industry vis-à-vis the US. I am thinking of German, Italian and Japanese automobiles, French luxury goods, European wines, cheeses, Swiss watches, Japanese and Korean consumer electronics products, etc. It would mean higher prices for American consumers, but that is the “stealth consumption tax” that Trump is imposing on them through his tariff war. The second reason why these countries and companies are relatively safe from the tariff impact is that most of them already manufacture in the United States to cater to the large and growing domestic market. To the extent that they import any components and parts from outside, they will face the same issues as the second group of countries that are part of global supply chains.

Trump has said in an interview with Bloomberg News that in order to avoid higher tariffs, many companies would invest in the US and set up manufacturing facilities there. This would be true if manufacturing costs were the same around the world, and we know that they aren’t. Which is why so many American companies prefer to make their products elsewhere and ship them to the US and around the world. Besides, as Tim Cook of Apple has said many times, the skill levels of the US workforce are just not the same as in China.

However, not all finished goods imported by the US are consumer goods; manufactures are listed separately by WITS (World Bank). In both these categories, a similar group of countries form the top 10 exporters to the US, led by China, Mexico and Canada. India is included in both groups, and since we don’t enjoy a huge competitive advantage in our exports yet, we ought to have an alternative plan.

I had a “what if” thought, which is that if countries actually take Trump up on his invitation to invest in America, can they not dominate certain industries in the US, the way Japan did in the late 1970s and through the 1980s? China would be the best candidate for this, but knowing that there will be huge restrictions on Chinese companies investing in America – and Chinese investment in the US has already fallen by much more than US investment has fallen in China , as you can see in the Statista charts below – they are automatically ruled out. However, the field is still open for companies from most East Asian countries such as Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and perhaps even India to step up investment in the US and take advantage of special skills, industry expertise and knowledge to go global and grow. All it takes are ideas for the future and innovation for this to become reality.

Still, what are the kinds of plans companies and countries can make in order to minimize the damage or disruption from the US import tariff increase? I suppose it would depend on the product category and how intricately it is engaged with global supply chains and would vary from company to company. I think in consumer electronics and automobiles, which is where the global supply chains are most predominant, it might mean that companies and countries have to find new markets for their products/components. And depending on how important the product or industry is to an economy it might even mean “derisking away from the US”. How about that, when until recently everyone was only talking about derisking away from China?! Given that Japan and South Korea dominate in automobiles, as does China in EVs, and all of these countries along with Taiwan and Singapore also dominate consumer electronics, we might just see the resurgence of Asian economies, along with Europe that also has strengths in automobiles.

I think in the corporate world senior leadership will be preoccupied with drawing up scenario plans for various ways in which the tariff war could break out. They will also be required to discuss plans and implications with their counterparts in government and take necessary steps to minimize the risk from tariff increases, and when and how to retaliate, if necessary.

Now, let us examine what such wide-ranging tariff increases on all products and all countries across the world could do to consumer price inflation. I think if the US goes ahead and implements all these tariff increases across the board, and if many countries decide to retaliate, we will see producer price and consumer price inflation in the medium to long term. This, when countries are still trying to tame inflation and stoke growth, with central banks lowering interest rates. The more immediate impact might be a seizing up or stalling of trade, especially between US and China, on whom the tariff increases will be massive. Supply chains too might get disrupted in the immediate to short term, until alternative arrangements are made. The tariff increases coupled with deporting immigrants and reducing immigration could in fact adversely affect the US labour market and wages. I just hope that recent wage gains seen in America don’t go in the reverse direction. In fact, the resulting stalling or slowing down of international trade and economic growth, could well take the form of stagflation, which is the last thing the world needs right now.

When it comes to the impact on China, I think many MNCs including Chinese ones might once again relocate to other countries in search of more cost-effective manufacturing destinations that also avoid the 60% tariffs on Chinese imports. That said, since China has built a competitive advantage in hi-tech industries including EVs, semiconductors and renewables, it has helped them weather the terrible slowdown they are seeing in their domestic economy. As I have written before, this entire tariff war will once again help China globalize faster, with its corporate champions going global. In fact, connected with my point on global supply chains in the automobiles and consumer electronics industries now having to concentrate more on East Asia and Europe, China will continue to be an integral part of it. China also has the economic heft and size to retaliate as it did in the first round of Trump’s trade war, and it will choose to do so more carefully and strategically.

As far as India is concerned, I tried searching for details of India-US trade in goods and from what little I could find, they mostly seem to be in commodities, pharmaceuticals and energy, besides gems and jewellery and apparel. I don’t think we would be impacted very much except for pharmaceuticals maybe, especially if these are of the intermediate goods type. Economist Arvind Subramanian has written recently that India should try and negotiate an FTA with the US, in order to benefit from the good relationship that our two countries’ leaders enjoy, but I think we should think long and hard about India’s long-term interests and only then decide on next steps. I think that we should aim to attract companies leaving China in search of better destinations in which to manufacture and do business and I agree with him on this. We missed out, the last time around.

I also think that our information technology and perhaps even pharma companies can accelerate their investments in the US and build stronger markets there. Indian IT firms are already investing and operating in America and creating jobs there. Our engineering companies and automobile companies should aim to do the same, though I don’t think any of this should mean neglecting the Indian home market. It is a good time for India Inc to dust off their global plans and actually pursue them seriously and to repatriate their profits home.

Finally, I must say that while contemplating all of this, I am not at ease with a high-tariff system that aims to keep competition out, reduce investment and trade and international cooperation. Which brings me to my last point about the new tariff regime having the potential to seriously disrupt the global economy, including relations between countries. Worse, it will erode the effectiveness of the multilateral rules-based system that the US set up in the first place, decades ago.

With US taking an isolationist stance in economic terms, it will reflect in foreign policy and security matters as well. The last time, China was hit badly by the Covid pandemic which then spread around the world. This time, China is in an economic funk, but it won’t be long before it steps into the vacuum being created by the world’s largest and most powerful economy.

The featured image at the start of this post is by Anna Shvets from Pexels.