While I was still contemplating buying Amitav Ghosh’s newest book, The Nutmeg’s Curse, my father had already ordered it from Amazon India. Well, I’m not complaining. I greatly admire his writing, having owned and read several of his books, before I lost almost all of my books to termites at my parents’ flat in Goa.

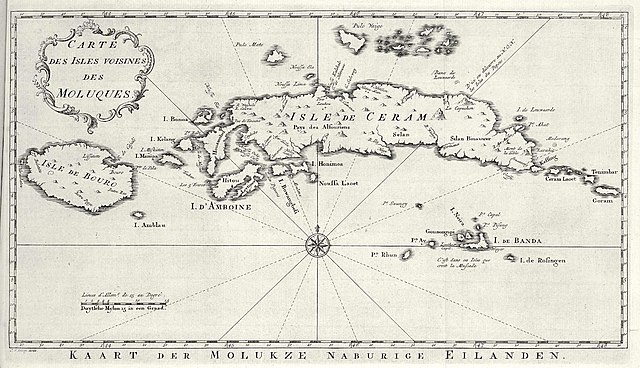

The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis begins with the Dutch East India Company’s colonisation of the islands of Indonesia. It begins in rather dramatic fashion in the Banda Islands, a tiny speck of an island on an atlas, just west of Irian Jaya, in the Banda Sea. In 1621, a Dutch official, Martijn Sonck, sent to drive away the local population from the island, sees a lamp fall. And the rest, as they say, is history. In a tragic case of mistaken judgement, Sonck and his men think the islanders are out to attack them, and they unleash a wave of terror on the island.

“On the night of April 21, when Sonck retires to Selamon’s commandeered meeting house with his counselors, his state of mind is very precarious. There is so much tension in the air that the silence seems to augur a seismic eruption.

The atmosphere is such that for someone in Sonck’s state it is impossible, perhaps, to see the falling of an object as an ordinary mishap – it has to be a sign of something else, betokening some sinister intent. So when the lamp falls, Sonck jumps instantly to the conclusion that it is a signal, intended to trigger a surprise attack on himself and his soldiers. He and his panicked counselors snatch up their firearms and begin shooting at random.”

Dutch and European demand for a particular spice – nutmeg – brings them to Banda Islands. Ghosh’s description of the islands and the nutmeg trees themselves are beautiful. The fact that the nutmeg plant thrives in what are volcanic islands, growing in volcanic soil is even more remarkable. The Gunung Api, as Ghosh tells us sits in the Ring of Fire that runs from Chile, in the east, to the rim of the Indian ocean, in the west. “A still active volcano, Gunung Api (Fire Mountain), towers above the Bandas, its peak perpetually wreathed in plumes of swirling cloud and upwelling steam.”

From the Banda Islands, Ghosh takes a detour to America to examine the fate of the native American Indian, when British and European settlers landed on the shores of America. He writes of the same greed for land, for natural resources and for commodities driving the native Indians off their lands. Ghosh also tells us how centuries of native wisdom regarding nature and the earth, of its deeply held secrets, were lost when native populations were ousted, marginalized and killed. He writes that the native American Indians had a different relationship with the earth and with its natural bounty.

In chapter 2, titled Burn Everywhere, Their Dwellings, Ghosh makes this unimaginable leap from the Dutch in Banda Islands to the Pequot War of 1636-38, via the Thirty Years War and the presence of the Dutch in New Netherland, in New Amsterdam in Manhattan.

The common thread between what transpired in Banda Islands and in Connecticut was not just the presence of the Dutch and British colonists, but the idea of “terraforming”, as Ghosh puts it. The idea and process of shaping the land to suit one’s own requirements, and how European colonisers and settlers pursued this with single-minded determination. Quite in contrast with the native American’s relationship with the land: one of gratitude, of preservation and respect.

In a chapter titled Bonds of the Earth, the author writes of the decline of the Dutch East India Company, not least due to the changing tastes of the Dutch and Europeans and their avoidance of the nutmeg. However, as Ghosh is quick to point out, the Dutch and their European conterparts had underestimated the propagative power of trees and of nature. Much to everyone’s surprise, the nutmeg which had travelled far and wide by now, began to grow in Barbados and in Connecticut, causing the author to observe that Barbados had now become nutmeg island and Connecticut, nutmeg state.

If the book, The Nutmeg’s Curse, at times seems as though it is rambling a little aimlessly, it is because it does meander somewhat like a river. Ghosh, through the history of colonization, tells us about the idea of terraforming, of ecological plunder, of man constantly trying to triumph over nature and control it. Between the narratives of the Banda Islands, America and the Caribbean, Ghosh explores man’s relationship with the earth as imagined in the literary world as well. For what drove colonists to acquire land and wealth, also existed in the wider human imagination. From Francis Bacon and his belief in the superiority of race and need for colonization to terraforming as explored in the ideas of HG Wells’ War of the Worlds, Tennyson’s In Memoriam and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, Ghosh delineates these strands of popular and even dominant thought at the time. Ghosh tells us that Tennyson was also a man of science who believed in Darwin’s theories, yet in his poem, In Memoriam, published ten years before Darwin’s Origin of the Species, it is man who rises above all else, who has grown with time.

Besides the occasional meandering, most of the book is anchored in the theme of terraforming, whether by the colonialists building their empires, or by modern-day capitalism and big business. In chapters 8 to 12, Ghosh deals with issues of our time. Contemporary and burning issues, such as dependence on fossil fuels, climate change, natural disasters and the increasing frequency of extreme weather events that the world is still grappling with. Change is coming, but it is at a glacial pace, and what’s more, almost all of the critical aspects of the science of climate change and the environment have become the preserve of a few scientific experts. What the author means to say is that issues to do with environment policy have been walled off from ordinary citizens and stakeholders, especially the poor whose lives and livelihoods depend on the earth such as farmers, fisherfolk, indigenous people and migrants. Ghosh also writes of how climate change policy itself is framed to suit certain vested interests; how emissions related to military and defence activity, for example, were deliberately kept out of the Kyoto Protocol at the behest of the country with the largest military-industrial complex in the world, the United States of America.

In later chapters, Ghosh returns to subjects that concern the poor and the vulnerable, such as migration. The concept of poor economic migrants taking on perilous journeys by flimsy boats and dinghies across continents raises racist reactions in the first world, since they are mostly from poor countries in Africa or the Middle-East. Yet, it is time that the world anticipates and prepares for new waves of large-scale migrations across the world driven by climate change. When it will simply be impossible for certain parts of the world to be inhabited, when even our cities face the threat of rising sea levels, what shall humankind do?

Ghosh fears that internal displacement, or circulatory migration will become the solution to acute climate change even as it increases the exploitative aspects of labour, as is already prevalent in many parts of the developing world.

“Adaptive measures, at the individual and the national level, are essential to cope with the deepening crises that loom ahead. Without them, national boundaries will continue to be the primary battlegrounds of the planetary crisis, where growing numbers of people will face an irregular war that condemns them to the fate implicit in the Latin word for border – terminus. From this derives another word, extermino, which means drive over the border, exile, banish, exclude. Hence the English word, exterminate, the exact meaning of which is “to drive over the border to death, banish from life.”

In the last chapter of the book, Hidden Forces, Ghosh returns to Banda Islands. To write about the island’s people, often of mixed races and cultures, and their legends and stories. Of foe-foe, or Banda magic and orang halus or ghostly spirits that still govern their lives. The chapter actually gets its name from a book called The Hidden Force, by a celebrated Dutch writer Louis Couperus, published in 1900. It is about a middle-aged colonial official Otto Van Oudijk in a small town in Java, whose life slowly disintegrates, as he tries to understand it and come to better terms with it. As Ghosh writes,

“Van Oudijk’s crisis is not just personal; he is forced, rather, to confront the epistemic violence of colonialism. He who believes himself to be in a place that has been subjugated and brought to order long ago, now finds himself dealing with forces that he can neither control nor understand. He is unable, despite his best efforts, to mute the voices that are making himself heard around him.”

Small poetic justice, that. The bigger lesson from The Nutmeg’s Curse is to heed the signs of environmental change if we are to avoid an apocalypse this century.

On that note, I shall go read Amitav Ghosh’s 2016 book on the environment, The Great Derangement, next.

The featured image at the start of this post is of Banda Islands by Georg Holderied CC by SA 2.0 on Wikimedia Commons

For a fairly good understanding of American Indian history, I would recommend a book called Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown. Amitav Ghosh doesn’t mention it anywhere in his reference notes or bibliography, but I think interested readers might enjoy it.