More importantly, can it afford to?

At the start of the 2007/08 Financial Crisis, many international commentators talked of the possibility of deglobalization, perhaps out of fears that the global financial system had grown too large, too fast, and that tougher regulation might force them to shrink their operations. Whether the regulatory system forced them to shrink or not, many large global banks did reduce their assets and their global footprint. I remember, RBS (Royal Bank of Scotland) for one, which made the mistake of acquiring ABN Amro, sold most of their assets overseas, including in India, where their country head, the late Meera Sanyal, decided to enter politics by joining AAP (Aam Aadmi Party).

Much of the deglobalisation talk actually had more to do with US and China decoupling; many commentators and economists thought that the world’s two largest economies might decouple, though how that would happen given that they are inextricably linked, was anybody’s guess. In 2008, US-China trade was US $ 407.5 billion, and China’s holdings of US treasuries was US $ 1.7 trillion.

Since then, the two countries have certainly drifted apart, in no small measure due to Trump’s trade war with China, but deglobalisation? Really? Trump’s trade war is the closest the US has come to decoupling from China, and with Biden’s latest policies, the trade war is steadily morphing into a cold war, as I just wrote in my last blog post. However, it is more rhetoric than reality. Make no mistake, the world is not deglobalising.

All this talk and conjecture about the prospects of deglobalisation stem from three important factors. The first and most important one is the US-China trade war and the chances of their decoupling, as a result. Although it appears we are heading into a US-China cold war era, it would be incorrect or hasty to assume even from Xi Jinping’s speech at the 20th Communist Party Congress that the two superpowers are decoupling.

The second equally important factor is the backlash against globalization in rich, Western economies where the narrative that has been deliberately propagated by their politicians, is that hundreds of thousands of jobs were lost because they were shipped to China. The fact that many more were lost to technology and the financial crisis, conveniently never crossed their minds. Politicians in western countries failed to explain to their people why globalization made sense, nor did they prepare them for better jobs in new industries that were beginning to grow in the Western world. Instead, they rode the populist wave against globalization, by talking up nationalist nonsense and shutting the doors on immigrants.

This is the nationalist, anti-globalisation wave that elected Trump in the US and brought on Brexit in the UK. Brexiteers always talked of a “global Britain” after Brexit, though, and it’s hard to see how the two conflicting sentiments reconcile. In Europe too, this anti-globalisation, nationalist sentiment exists in many countries, from France and Germany to Hungary and Italy, where populist right-wing parties prey on the fears of their people. And it manifests itself most visibly and loudly as anti-immigration.

The third more recent consideration that has once again brought back talk of deglobalisation is supply chain issues, post the Covid-19 pandemic. Thanks to the surge in demand once Covid lockdowns were eased especially in Western countries, it has exposed the weak link in manufacturing, though manufacturing is what held steady during the pandemic. Global supply chains of semiconductors, most of which is centred around China and a few East Asian countries such as Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, struggled to keep pace with the sudden rise in demand and these east Asian countries were all still terribly impacted by the second Delta wave of the pandemic at the time.

Soon there were people deriding the globalized, just-in-time manufacturing model, and politicians especially in the US wanted to bring home more of the semiconductor manufacture. They also saw it as a chance to compete with China, since it was still struggling with severe Covid lockdowns as a result of pursuing zero-Covid policies. The US has not only passed the Chips Act, it has banned the sale of high-end semiconductors to China, and it has made trips to Taiwan to provoke Beijing.

And while I agree that manufacture of chips and semiconductors of all types, which are needed in vast quantities to manufacture an entire range of products nowadays, from cars and consumer electronics to industrial, utility and telecom equipment, ought to be more diversified across many more countries/regional hubs, it is still not deglobalisation. The US, Europe, and perhaps even India with their capabilities in the industry could be possible new hubs of semiconductor design and manufacture, in addition to what we have in China and East Asia and that would be the way forward.

Here’s why I think globalisation is not going to be so easy to reverse.

Good or bad, the fact is that globalisation has brought immense growth to countries around the world, both rich and poor. It has brought tremendous growth to multinational companies and countries, made products accessible and affordable for millions of consumers, and has created millions of jobs in poor and developing countries as well as emerging economies. It could, and should have been managed better, but on balance, there is no disputing the fact that it has been a force for good.

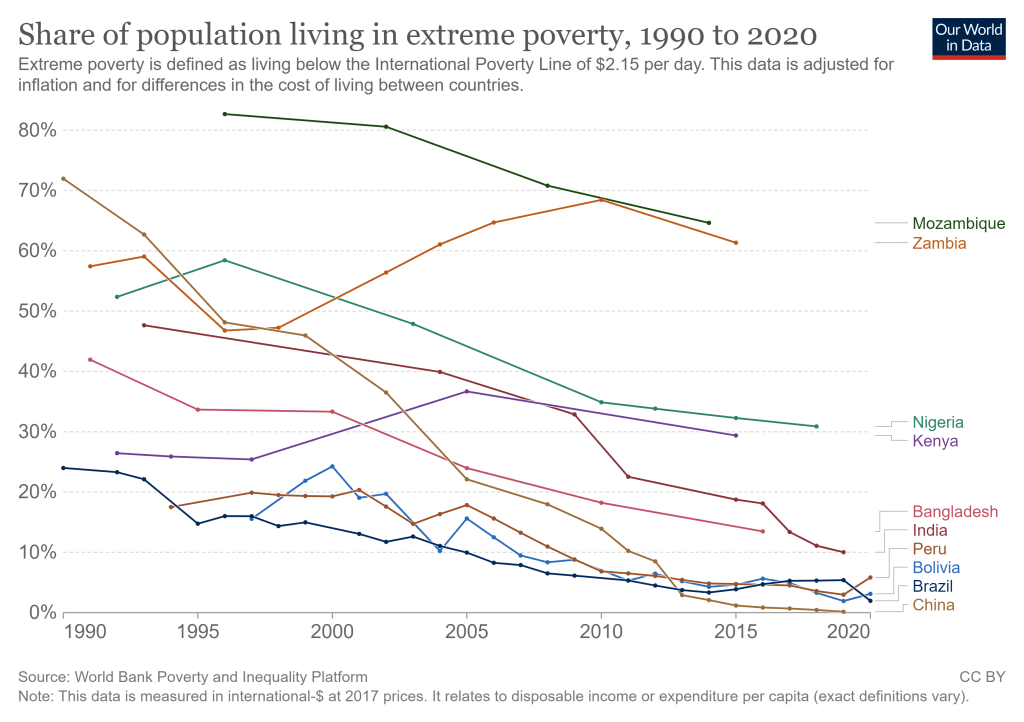

Between 1990 and 2021 (the last year for which WTO has data), the three decades of globalization, world trade by value has grown seven-fold from US$ 3.5 trillion in 1990 to US $21.85 trillion. Global capital flows (FDI net inflows) have also grown almost six-fold from US $239.42 billion in 1990 to US $ 1.14 trillion in 2020 according to the World Bank, which includes the highs of US $3.13 trillion reached in 2007, and US $2.75 trillion in 2015, with very steep drops in between. What’s more, if you look at the WTO charts (shared below from WTO’s website), you realise that world trade did not drop by very much even during the 2008 financial crisis nor the Covid-19 pandemic, which is to say that globalized economies were cushioned by world trade, even during severe economic downturns, when investment was adversely impacted. Millions in developing countries have been lifted out of poverty from Latin America to Africa and Asia, as you can see in the chart from Our World in Data. In other words, there is too much that is good that will be lost or sacrificed, if companies or governments were to reverse their policies and pull back from globalization.

On the flip side, one of the adverse side-effects of globalisation if you like, is the massive increase in inequality of income and wealth. A larger share of national income of most countries, has gone to capital and not to labour, and this is particularly so since the 1990s, as several studies including that by Thomas Piketty in his book, Capital in the Twenty-first Century, show. The top 10% or even 1% of any country’s population has a disproportionate share of national income and wealth. So, while globalization has helped poor and developing economies, it is not a rising tide that has lifted all boats equally and that certainly needs to be addressed.

Although this ought to be an issue that governments ought to regulate better through legislation, the fact is that on many such matters, businesses and governments collude or act together. Their relationship is complex since they both need each other in order to grow, though they are on opposite sides of economic regulation. Therefore, it is always a relationship marked by courtship, lobbying and pressure tactics, negotiations, and sharing of the spoils. As I have written before on my blog, since the days when business aristocrats lobbied King John of England through the Magna Carta for greater freedom and rights, this has characterized capitalist enterprise. Quite often, we also have crony capitalism as a result. Governments have been party to globalization and to business interests, and they are not likely to let go so easily.

Another adverse side-effect is that many multinational companies have exploited the loopholes in countries’ taxation laws to avoid paying income tax in many jurisdictions, if not evade them outright. The idea of a Minimum Corporate Tax, recently mooted by the US and accepted by almost all G20 countries and others is one way of resolving this vexing issue of tax avoidance by multinational corporations. It states very simply that where a company makes sales of its products or services – and not necessarily where it is incorporated – it is liable to pay a minimum corporate tax of 15%.

In the context of the forthcoming G20 summit 2022 in Bali, Indonesia, where “Recover together, recover stronger” is the conference theme in obvious reference to the post-pandemic economic recovery, the three pillars on which it rests are health infrastructure, sustainable energy transition and digital transformation, it is important for countries and businesses to see how economic recovery can benefit all sections of the population. The G20 is a grouping of economies, rich, emerging and developing that together produce 70%-80% of the world’s GDP. More important, together they have a voice that doesn’t reflect only the interests of the rich, advanced countries (G7), but is more representative of the global economy and its interdependence.

India hosts the G20 next year in 2023, and my hope is that it will be an occasion to celebrate the good of globalization as well as remedy its failings. To that extent, India will do well to address issues of inequality, climate change and labour laws and human rights. More particularly, the India G20 summit would take a big leap forward if it could help set certain minimum standards for businesses to adhere to, in each of these areas. Of course, these will have to be followed through by ratification in parliaments of member countries/legislation. This would mark tangible progress on the path of globalization, just the way the Minimum Corporate Tax does.

Another area of discussion in the context of globalization is the services industry; usually when we talk of globalization or international trade, goods and merchandise dominate. Partly this is because trade in services is still a stumbling block at WTO, and there are no international guidelines to regulate most of the sector. At the same time, we know that information technology, the internet, media and communications as well as financial services are all global in today’s world, and services increasingly contribute larger shares to countries’ economic output.

Speaking of financial services, it is the most global of modern finance and its flows and impact throughout the world was evident in the 2008 Financial Crisis. More recently, it was also indicative of the powerplay between governments and the markets, when international markets reacted violently to the former UK Chancellor of the Exchequer’s mini-budget.

If we needed a sign that globalization is alive and well, this provided it. And more will follow in the months and years ahead, as the world tames inflation and finds ways to boost growth. Globalisation is not in retreat. It needs more global coordination.