As I have written in a previous blog post, we have begun the New Year on a rather dramatic note, at least geopolitically. And a lot of these kinds of developments are likely to have serious ramifications on the economic front as well. In fact, geopolitical as well as geoeconomic risks are the greatest risks facing the world economy. This has been the case for the past couple of years at least and is only likely to grow in 2026 and the years ahead. Therefore, it’s going to be hard to navigate one’s way to growth amid all these tensions and challenges.

As the World Economic Forum meets at Davos, Switzerland, for its annual meeting in January 2026, the Global Risks Report 2026 released ahead of the summit, makes for important reading. I am not sure who the experts responding to the WEF survey are – as in business heads or policymakers – but it highlights the biggest areas of concern among the Davos elite. It appears that this survey hardly changes very much from year to year, and the analysis too is wanting, but it seems that geoeconomic confrontation is the biggest short-term risk, followed by misinformation and disinformation as well as societal polarization, while the top longer-term risks are all environmental, which the report rightly reads as the deprioritisation of environmental issues in the short term.

The World Economic Forum has also released its Chief Economists’ Outlook 2026, which makes for an even sketchier picture and offers an inadequate view of the global economy, at least as far as policymaking is concerned. I think the structure of the survey and the report suffer from a very basic flaw in that the line of questioning and the inferences drawn from the survey of economists only tell us how many economists think a particular economic outcome will come to pass or not. Strangely the reports says that South Asia stands out as the strongest region in terms of economic growth outlook when so many south Asian economies are under the weather, unless of course, they mean only India. I decided not to write about the WEF Davos Summit this time, as I have found the panel discussions very disappointing for the past few years when I did write about them.

Surprisingly, the IMF World Economic Outlook January Update 2026 too is out, when the main WEO is usually released along with the World Bank Group Spring Meetings that take place in the US in April each year. It outlines for us the economic growth possibilities and risks across different regions of the world. The greatest risks are easy to anticipate – high debt levels, fiscal profligacy, geopolitical tensions and the AI investment bubble, if it turns out to be a bubble at all.

Their analysis seems to suggest that US and Asia are witnessing an AI-related tech boom that ought to enhance productivity and economic growth in these regions. The update also says that a lot of the tariff-related risks have been offset to some extent by AI-related productivity growth. I am not sure this can be generalized across the board and would probably hold good only for large companies chiefly those in the US. The report doesn’t dwell on the risks of AI technology adversely impacting jobs although it does mention it in passing. More importantly, though, the IMF WEO January 2026 update does flag the risk of the AI investment boom itself turning sour, given that valuations have soared through the roof. I think there is also the danger of too many cross-investments by and across AI and tech firms which is probably fuelling the stock prices of these companies, which in turn increases the risk of a domino-effect collapse in case the bubble bursts. The reason why many think there might be an AI bubble is because of overinvestment by AI firms, when AI deployment by companies according to McKinsey is limited to a few kinds of functions and industries.

The IMF thinks that elsewhere, the going will be slow and tough, given the geoeconomic and political tensions and risks, as well as weak consumer demand and weak private sector investment. It is a good sign that consumer price inflation is slowly trending down across the world, though the tariff impact in the US is yet to be fully felt as many companies have still not passed on higher prices to consumers. Many economists think that CPI will start to tick higher this year in the US on account of tariffs being passed on, as well as significant tax refunds that most Americans will receive as a result of Trump’s generous tax cuts.

I would like to look at the world economy in 2026 and beyond, from a slightly different perspective. The most important factors for me would be: 1) how much private sector is able to pick up the slack in investment especially after governments in most parts of the world invested and spent hugely during the Covid-19 years and thereafter; 2) how the private sector navigates the fractious geopolitical climate, when governments are increasingly dictating terms and 3) how the private sector invests in AI and other technologies without damaging human intelligence, human capital and man’s capacity to innovate.

What I mean is that although the news flow and the geopolitical climate are being dominated and determined by governments, the actual growth prospects will come, as always, from the underlying strength of business and the corporate sector. And to my mind, the relationship between business and government might be at an inflection point, when nationalist policymaking might be at odds with what makes better business sense. Of course, a lot of it has to do with Trump and his economic and foreign policies and the upending of the world economic order that we are all witnessing. Equally, it has to do with the disruption of tech, especially AI, and its impact on jobs and entire industries. The collision of both these essentially disruptive forces at the same time is going to be more than governments and businesses can handle.

In this sense, I think that 2026 will be a year when global business and international relations between countries will be severely tested. It will also manifest itself in the relationships that businesses, governments and citizens have with each other, where all these relationships will come under greater strain.

Allow me to explain. In a world where unilateral tariffs by one economic superpower will force other countries to respond in certain ways – either through retaliation, compromise or diversifying away from the country as much as possible – businesses are not only going to be operating under higher uncertainty, they will be forced to take certain business decisions because of their home country’s government’s policies and geopolitical tensions. So much of these decisions might not be the best for business. I can think of India’s large tech companies, for example, that already invest hugely in the US, but are going to be impacted by the new, tighter H1B visa restrictions, also because they involve huge amounts of money.

On the other hand, the tariff war and geopolitical tensions could also threaten business prospects and expansion plans when they involve retaliation of some kind. Many decisions of the US, for example, have forced China to take a tougher stand on rare-earths, electronic components and the like, which affects not just the US but businesses around the world. India’s automobile industry has suffered setbacks because of China’s restrictions on rare earths which are used in the manufacture of many electronic components even if India was not the main target of the restriction. In other words, tariff wars and retaliation as well as protectionist barriers affect businesses the most, and through their performance, economic growth of countries around the world.

This doesn’t mean that businesses themselves shouldn’t be doing more to increase investment, create more and better jobs and grow their companies. In recent years, governments have done the bulk of investment and spending across most countries, especially since the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020. Most of it has either been in the form of huge capital expenditure on infrastructure or higher social spending to protect jobs during the terrible pandemic. As a result, many governments, especially those in the West, have racked up mountains of debt and burnt holes in their public finances that they must reduce and resolve soon. Private sector investment needs to step in and do its bit to create new business and expand operations, create better employment opportunities and improve people’s lives.

Private sector investment is certainly not growing at the rate that it should. Not in the advanced economies and not in emerging economies either. Except, of course, in AI and big tech in the US and elsewhere. However, lack of adequate growth in private investment is not recent; it goes back to the aftermath of the 2008 Financial Crisis, when in the recovery period it was widely reported that companies were sitting on huge profits – a lot of it stashed away in tax havens around the world – and were busy rewarding shareholders and engaging in share buybacks instead of reinvesting back in the business.

Along with all the short-termism that we see in business globally, this lack of adequate investment by firms in improving and expanding their business capacity has to be one of the most serious problems looming over the private sector. As a result, frequent share buybacks have made the rich even wealthier, while businesses suffer from lack of innovation, lack of ideas, lack of employee morale and good quality jobs, and a general inertia if I might call it that, that saps business vitality and growth.

Overinvestment in AI and lack of investment elsewhere risks the danger of accelerating job losses when there are no new ones to be had, laying waste to millions of educated and talented people who are not being adequately reskilled or upskilled either. It is quite unfortunate that AI is not being used enough in R&D and innovation, as is clear from the same McKinsey report cited earlier in this blog post. McKinsey itself doesn’t treat R&D and innovation as a separate function, though respondents in their survey say that AI has helped them in innovation (where it appears along with other outcomes). I took product/service development as a proxy for innovation and even then, the use of AI seems low, except in the tech and pharma industries. Further, according to this article by JP Morgan which I happened to see online, private investment in AI in the US has reached such high levels, as to contribute more to GDP growth than private consumption which was the big driver of economic growth for decades. This of course is because private consumption growth in the US might be slowing down right now, and also because AI investments are stepping up, in an environment that is independent of interest rates and tariffs relatively speaking. What is also required is increased investment by companies in innovation in their core businesses. AI alone cannot and will not save the world; unchecked, it is instead fuelling unhealthy competition between companies and countries all consumed by the need to stay ahead in the global AI race.

This brings us to the tensions in the relations that businesses and governments will have with citizens everywhere. Large numbers of unemployed and underemployed folk are going to pose huge problems for everyone. Countries that have social safety nets will have to bear higher burdens of social spending at a time when governments need to drastically reduce their social spending. Those that don’t have adequate social security systems will face growing ire and distrust, leading to frayed societies and social unrest. The WEF Global Risks Report talks of societal polarisation as a significant risk; this deals with political, economic, social and cultural divides in our societies. But I think it could be something much worse: social alienation. This will put greater pressure on the relationship between governments and businesses, even though it is the main responsibility of the former to look after the interests of citizens.

Populist policymaking is not the answer. A lot of what we see of Trump’s policies, from America First economic and foreign policies to mass deportation of immigrants as well as replacing taxes with tariffs, is aimed at the MAGA crowd that is his political base in America. Unfortunately, as I wrote in a recent blog post about the economic impact of far-right parties and their policies, MAGA voters haven’t made much economic headway in the US since Trump’s first term as President of the country. Neither is nationalist or protectionist policymaking the solution. Whether it is the US government taking a 10% stake in Intel, a 15% commission on Nvidia and Qualcomm’s sales to China, capping credit card rates at 10% in the US, asking US oil companies to invest in Venezuela’s oil industry, these are all signs of the government forcing the private sector’s hand and exercising control of firms and are likely to create unnecessary market distortions in the US, otherwise hailed as the land of free enterprise and laissez faire capitalism.

America is already witnessing an affordability crisis, and Trump has had to roll back or reduce several tariffs in response. Besides, the government’s brutal crackdown on protests and forced detention of immigrants in several cities and states across the US suggests a country already at war with itself. Trump’s trampling on the independence of the US Federal Reserve and attacks on its governor, is another sign of instability that the world should be very wary of.

The conflicts between the government, its citizens and business are already playing out in America. And this, as it celebrates 250 years of its independence in 2026. This illustrates what I have been writing about in this piece. And no matter how much Trump criticizes his allies such as those in Europe, and no matter how much he covets Greenland, his biggest problems lie at home especially with the US Mid-term elections later this year.

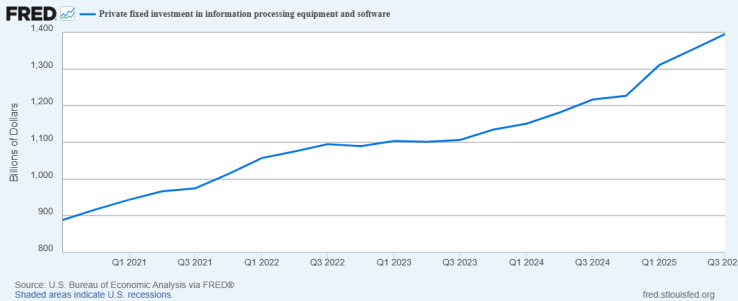

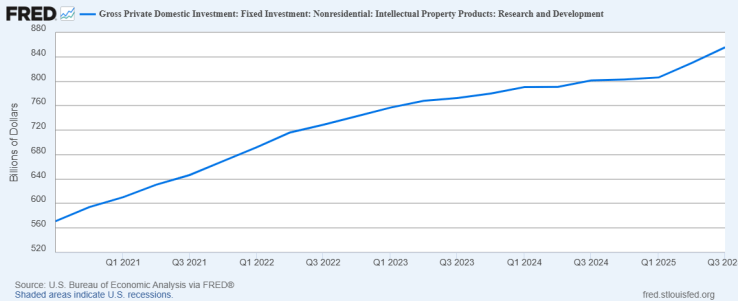

It is in these kinds of tensions between governments, business and people, that we need to focus on work: on innovating, investing, creating employment and growing our economies. Everyone seems to be pinning their hopes on AI as the saviour, but there is another kind of intellectual property that might be better at building affinities in a world of fraying societal ties. I am not saying this only because I am an advertising professional, but growing businesses by building brands is just what the world needs more of, right now. If businesses invest more in AI than in innovation in their core businesses which is what generates their bread and butter, we could be in for troubling times where AI investments outpace consumption growth and production. For Q3 2025 US GDP growth which has finally come in at 4.4%, private fixed investment in information processing equipment and software is 25.46% of total private fixed investment, while R&D is only 15.6% of total private fixed investment and while both are growing, the latter is growing much slower than the former in the past few years. I think general innovation and R&D ought to receive greater attention and investment.

If companies can stay focused on their strategies for growth – without getting sidetracked by geopolitical issues – and innovate, build brands, connect better with customers, and grow their businesses we might have a better 2026 than it appears right now. And if companies in the services sector can build and strengthen their brands and businesses, not just because they are outside the purview of tariffs right now but because services build connections and affinities better and easier, economies around the world could see better and more sustained growth this year and beyond.

The featured image at the start of this post is courtesy Flickr on World Economic Forum’s website