In a recent blog post of mine I had written about the US and its western allies’ allegations of China dumping its cheaper EVs, EV batteries, semiconductors, solar panels and the like on their markets. They have raised tariffs on Chinese EVs from 25% to 100% in the US and to 38% in the EU and I am certain tariffs on other Chinese goods will follow.

I have also written that China will retaliate with similar hikes on its imports from the West, and that this new wave of the trade war with China will do no country any good. Besides, if it is true that Chinese EVs only make up 2% of EVs in the US whose penetration itself is low, this is just paranoia and political posturing in election season. European countries, especially those with large car-making industries and who also have a significant presence in China, ought to know that their car companies could be hurt in the process.

Instead of going down this path of confrontation, restrictive trade practices and trade wars, we can try to understand why China is facing an oversupply problem in the first place and try and remedy the situation in a way that benefits everyone. It is obvious that because domestic consumer demand is still weak in China, hurt as it is by the long, zero-Covid policies that the country followed as well as the crisis in the housing sector, China is having to look elsewhere for economic growth. It appears that households are preferring to save more money than spend as freely as they used to in the pre-Covid years. And although the Chinese government has offered incentives for individuals and small businesses to upgrade their household appliances and machinery and the central bank has also kept monetary policy accommodative, it is taking a while for consumption to recover.

The latest consumer price inflation for China in June 2024 – a proxy for gauging consumption demand – has come in at 0.2% year on year, slower than estimates of 0.4%. Core CPI is higher at 0.6%, but even this is slower than the 0.7% recorded for the first six months of 2024. According to this Reuters article, companies are resorting to discounts in order to boost buying, and the Chinese government might reconsider their consumption tax soon. What else can China do to boost economic growth through domestic consumption and investment, and avoid overproducing EVs, batteries, semiconductors, etc that the local market is not able to absorb and is being dumped on other countries?

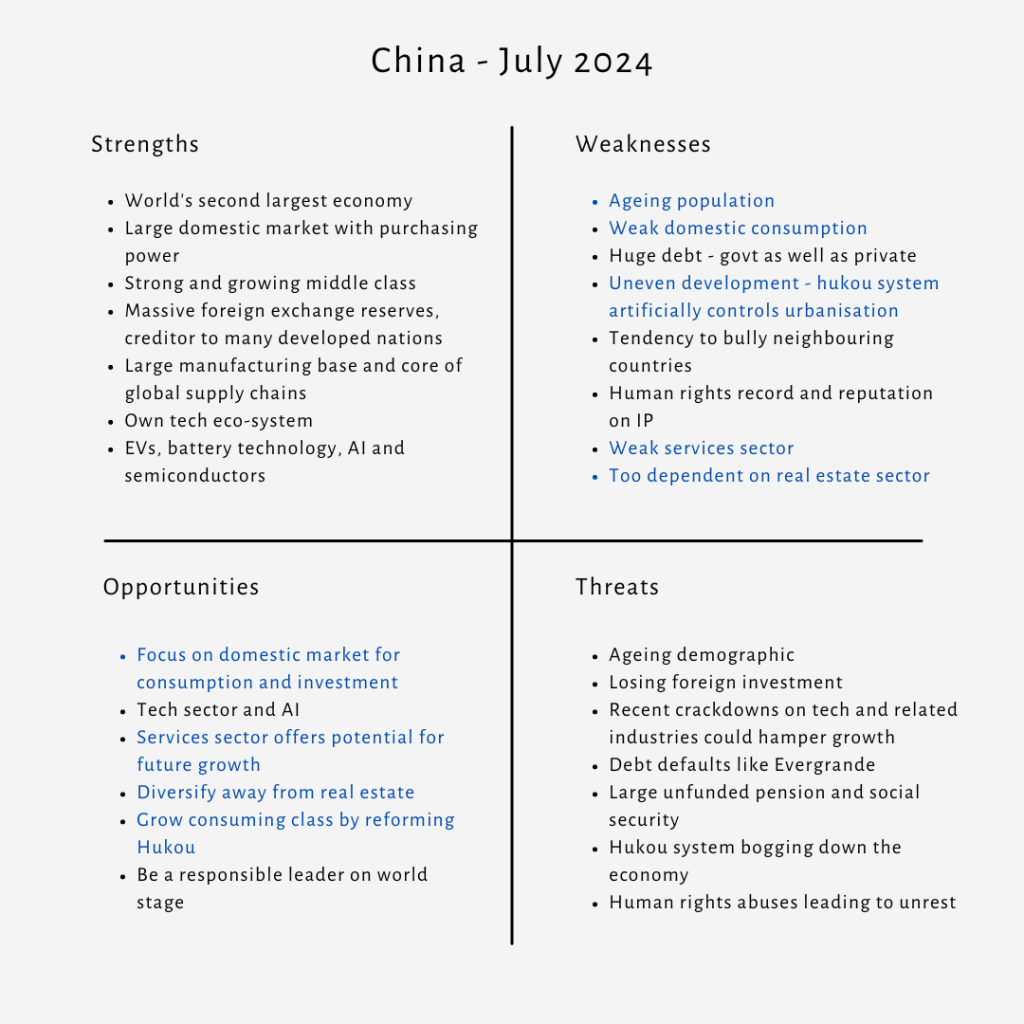

I had done a SWOT analysis of various economies and economic regions in a blog post, dated October 2021, and I thought it might make sense to revisit it. In my SWOT analysis for China then, I had said that AI and high-tech goods including EVs were opportunities. Now I find that they have become China’s strengths, in a matter of three years. Some of it is due to the rapid pace at which technology progresses, but China is also relying on its strengths and industries in which it is competitive, to boost economic growth at a time when the country is slowing down.

Instead of focusing on its strengths at a time like this, what if China looked at its weaknesses and the opportunities now, for it to grow its economy in a more sustainable, long-term manner? Surely, cranking out more of high-tech goods for export markets, when the problem is the domestic economy and consumption more specifically, can hardly be the solution. Certainly not for the medium and long-term.

Instead, China can focus on important areas that need attention, in order to boost consumer demand. I have created a more recent SWOT analysis for the Chinese economy and have highlighted these key areas in blue, in the weaknesses and opportunities quadrants for them to compare and consider. Instead of focusing on strengths to boost economic growth through exports alone, China can undertake certain reforms to address weak domestic consumption and investment more directly. And it can look at certain new areas as well.

Start by understanding the cause of the weakness in consumer spending

One of the most reported reasons for the weak consumer spending is low consumer confidence or sentiment arising out of the real estate crisis. Another could be low or slow growth in wages. Both these can be addressed through economic reforms.

The real estate crisis needn’t have occurred if the Chinese economy weren’t so dependent on it; the problem here is that local governments have no other way to raise funds for economic development since they cannot levy their own taxes. The Chinese government must correct this as soon as possible by allowing local governments to raise some taxes of their own and perhaps also share some part of the central tax revenue with them, as is practised by most countries, including my own, India.

Another problem related to the real estate sector is that Chinese citizens are also too dependent on it, as they have few other ways to invest their hard-earned savings. This too must be tackled by the Chinese government else they will also be faced by capital flight out of China. As far as wage growth is concerned, I had suggested a wage increase for all government employees, which could be extended to all employees of state-owned enterprises. This depends on how often wage revisions are carried out in China and by how much.

A 2010 article by the Reserve Bank of Australia on household consumption trends in China says that in the 1990s, consumption as a share of China’s GDP used to be 50% and it later dropped to 38%. One of the reasons cited for this is that share of national income going to corporates increased as the system of employers in China providing social welfare benefits to their employees was withdrawn in the late 1990s. It appears then that employees didn’t step up their spending under those heads, else consumption couldn’t have fallen to the extent that it did. While the shares of investment (GFCF) and trade in GDP grew, personal consumption dropped.

I think a plausible reason for the fall in consumption’s share might also be that China’s GDP was growing faster than consumption. It is also well-known that the household savings rate in China is quite high – as much as 30% like it was in India – because of the lack of a social safety net and many attribute the lower share of consumption to this. But as Arthur R Kroeber of Gavekal Dragonomics points out in his book, China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know, this is not quite borne out by the facts.

“Growth in household consumption began to accelerate just as the old social safety net fell apart. In 2001, the trend growth rate in per capita consumer spending was just 5.6% a year; by 2008, when new social programs had been launched but not yet fully funded, spending rose to 7.6%. By 2013, trend consumption growth had climbed to 8.4%, even though the household saving rate continued to rise. This acceleration is not consistent with the “precautionary savings” story… but it does square well with… how rapid industrialization can create large income gains that enable the average consumer to spend a lot more even as she saves more.”

Another reason Kroeber offers is that consumer spending in China is under-counted, since it was never the focus area for the government. I think that in the current context, another reason for weak consumption could be that the big cities where most of the spending was taking place were saturated. This can be an important factor in a country with stagnating population growth and an ageing demographic. This brings me to my next point.

Look at growing the consumption market

This is something companies and their marketing teams often consider, in order to grow the market for their goods and services. Why not an economy? If the big cities in China are saturated with consumer demand, there are scores of smaller cities to shift attention to.

According to a document by McKinsey on five consumer trends shaping the next decade of growth in China, China’s 30 largest cities are home to 25% of the country’s population who drive 45% of total household consumption. But they also point out that there are several tier 1 and tier 2 cities in China where consumer demand is likely to grow in this decade and indicate their potential on the basis of four dimensions. While these dimensions measure different things and are not strictly comparable – spending tendency, resources, actual expenditure and affordability – we can see the huge potential for development and growth in these cities. I think it makes immense sense for companies and businesses to focus their attention on newer geographical markets within mainland China for future growth.

And just as companies do while focusing on newer cities and towns for growth, it also makes sense to keep innovating with newer products and brands for the large, saturated markets.

In India, companies especially those in CPG and automobiles were focusing on Tier 1, 2 and 3 cities and towns for growth almost two decades ago.

Another equally important way to grow the consumer economy and more urgent in China’s current economic condition, is to regularize the Hukou system and give millions of migrant labour in China urban registration. This was mentioned by Zhu Min at the WEF Davos Summit earlier this year – as I wrote in my blog post on the conference – and I think it is an excellent way to immediately give consumption a boost, while also allowing for sustainable long-term growth.

Consider diversifying the economy

It is well-known that because China has been factory to the world, it has developed huge capabilities and skills in manufacturing, including in high-tech industries where it is an important part of global supply chains. However, its services sector continues to be weak, and not much attention or investment has taken place here.

Like most economies, China’s economy too can be propelled forward through its services sector. And these can cover a wide range of economic activities that are essential to improved living standards and quality of life. As I mentioned earlier, creating better investment avenues for Chinese consumers to invest their savings productively, rather than lock them up in grand housing projects which falter and fail, ought to be an important area of consideration.

Financial services – not of the wealth management kind that got China into trouble with its shadow banking crisis – but more stable and productive saving and investment ideas that help Chinese grow their savings and wealth over the long-term and reduce their dependence on the real estate sector is imperative. Along with insurance products of all kinds for Chinese people to save for a rainy day, for retirement, for their health and for property as well as reinsurance, knowing that climate disasters are going to be more frequent in the coming years. I was very surprised to read that basic health insurance in China has 95% coverage, which is good going indeed.

Other areas in the services sector that need attention are healthcare, considering that China is an ageing population, and education, though China does pretty well on this count. Newer areas of specialized and technical education as well as vocational education must be considered in response to the demands of the new age we are in, as well as newer consumer cohorts thanks to urbanisation.

Services that are oriented towards leisure activities is another area to consider when we are looking at ways to grow consumer demand. Travel, dining out and hospitality, as well as media and entertainment are also important services for an economy that is the world’s second-largest, but where these might have been ignored or neglected. These services would help Chinese consumers enjoy the rewards of their labour, grow culturally and socially, become more discerning consumers and more productive members of society. Their personal aspirations and goals would be addressed through diversifying in services, without necessarily having them glued to their mobile screens shopping for fashion, cosmetics and electronics all the time.

When speaking of services in China, it would be important to also consider logistics and transportation. Then again, since so much of China’s economy is powered by the internet and e-commerce, I would think the country already has a well-functioning logistics and transport infrastructure.

Explore brands as a way to boost consumer spending

There are several Chinese brands that are now well-known and well-regarded not merely in China but internationally. These are mostly in consumer electronics, appliances and EVs more recently; Lenovo, Vivo, Oppo, Xiaomi, Haier, Huawei, BYD and Nio and many more. The most popular of these, TikTok, is right now in the eye of a controversy, but that doesn’t seem to deter its fans and users. That said, I noticed how Chinese brands have attempted to increase their visibility through in-stadia branding at the UEFA Euro 2024 football championships now reaching its final stages.

While trying to boost consumer spending, China must explore and utilize the full potential of brands and brand-building to create more brands that are preferred by consumers and that also build relationships with them over the long term. Both in China as well as internationally. Of course, under the current geopolitical situation, there is every reason that Chinese consumers will prefer a homegrown Chinese brand over international competitors, but hopefully such jingoistic nationalism will not be the only and main reason for their preference. The ultimate test of Chinese brands will be in winning over discerning consumers in China who have grown up with the best international brands for many decades. After all, China was the large market dominated by international brands for so many years, before you had your own local Chinese brands. Unlike in India, where we had so many local Indian brands, before we liberalized and foreign brands entered the Indian market.

From what little I read online, it appears that China also has a large advertising industry, second only to the US and is expected to clock US$ 230 billion of ad spending in 2024. There is a huge yawning gap between estimated US ad spend of US$ 450 billion in 2024 and China’s, but this needn’t worry us. The fact that the Chinese advertising industry and market offer such huge opportunities is encouragement enough for Chinese companies and brands to focus on this dimension of marketing and boost consumer spending as well as build brand loyalty.

My only disappointment with China’s advertising potential is that almost 85% of it is already digital and probably mobile-first. In my view and as I have been writing on my blog for a long time now, digital is not such a great medium for consumer-engagement and brand building in the long term, so I would urge companies and advertising agencies in China to try a 60-40 kind of ratio in weightage and importance given to traditional advertising vis-à-vis digital communication. And the ratio is not in terms of advertising spends alone, since advertising on traditional media would still be expensive compared to digital even with low demand for it in China. I am not a marketing professional but I would imagine that this is the sort of ratio marketing departments maintain between marketing/brand-building and sales; digital performs the role of sales funnel adequately and therefore a 40% weightage should suffice.

The other huge area of opportunity while discussing advertising and brands is media and entertainment. A large consumer economy and market requires a large and vibrant media environment in which to operate. I don’t know much about media in China and media consumption habits, but I wouldn’t be surprised if most of this is also digital! Though from an advertising perspective, I wonder how this kind of focus on digital and mobile allows Chinese marketers to connect with older people in China who must form the larger consuming population with greater propensity to spend. Here too, I would urge greater liberalization in allowing more kinds of traditional media to operate, including cinema, TV, streaming, and radio. Besides, China has its own large movie industry which needs to be promoted overseas, and a cultural exchange of sorts between Chinese film and TV entertainment and the west would be a good way to build people to people relations between the Chinese and the rest of the world.

In fact, let me conclude this blog post with the conjecture, if not observation yet, that Chinese people and Chinese companies might navigate the geopolitical storms better, left to themselves. It is politicians everywhere who create the problems, just as it is with China isolating itself and having to look inward. Businesses and consumers might have better solutions – including for the oversupply problem that China is facing – that can actually benefit a lot more people.

The featured image at the start of this post of containers at Shanghai Port, Yangshan, is by Bruno Corpet CC by SA 3.0 on Wikimedia Commons