During the past couple of weeks, the world has seen such extreme weather events that I wonder if it isn’t high time, we looked at the economic consequences of climate change more seriously. The news has been full of terrible natural disasters such as floods caused by extremely high rainfall, wildfires and even if we don’t consider scorching temperatures a natural disaster, it is certainly part of extreme weather conditions that are the result of climate change and man’s inadequate response to it.

Right now, we seem to be so helpless against the fury of nature, but we cannot afford to stay helpless and hopeless for much longer. It is a question of survival for millions of people, especially the poor and economically vulnerable who are most impacted by it. There are the direct effects of such extreme weather conditions, such as loss of lives – both human and livestock – as well as loss of homes, livelihoods and infrastructure.

In just these past few weeks, many states of North India were hit by extreme rainfall and flash floods which washed away villages and small towns, cutting them off from the rest of the country, besides destroying several lives and displacing hundreds of thousands. The capital city of India, New Delhi, has been flooded by the rising Yamuna River. It is the worst flood some say, in the past 40 years, bringing the city to its knees and disrupting life and business alike.

In India, the monsoon is the most awaited event in summer every year. It brings relief from scorching heat, as also rains that Indian farmers depend upon. Indian agriculture is still almost entirely dependent on the monsoon rain, but when it is extreme and erratic as it has been this year, with thousands of acres of crops submerged, we can be sure that the economic impact will be felt far beyond these flooded fields. The immediate impact ought to be a shortage of food supplies, causing a spike in inflation. However, this effect might be somewhat delayed in India, since the government actively participates in foodgrain procurement, pricing and distribution, especially for the poor and it has built up massive buffer stocks in recent decades.

That said, the same cannot be said for other fresh agricultural produce such as vegetables, fruit, meat and dairy products, where it is largely left to private market forces to operate. And we do have the APMC (Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee) Act which controls the marketing of agricultural produce at the state level through mandis (local markets) that state governments earn taxes on. Repealing the APMC was meant to be part of the agricultural reforms that were initiated by the central government in 2017-18 but which were shelved after massive farmer protests in North India, and because of fear of electoral losses due to such a policy. Without getting into too many details of India’s agricultural policy, what I intend to communicate is the extent of government intervention in agriculture and food distribution and pricing.

Many other poor and developing countries might be following similar systems when it comes to subsidizing food for the poor and vulnerable sections of society. And while the nature of subsidies might be different, we know that agricultural subsidies are resorted to, even by rich developed countries from the US to Europe, China and Japan.

Then there are the transportation challenges and costs to consider, when massive natural disasters like these, strike. Increasingly, it will not be if or when, but a regular feature of life that we ought to be prepared to face such extreme weather conditions and their implications. Frequently occurring natural disasters mean frequent humanitarian disasters.

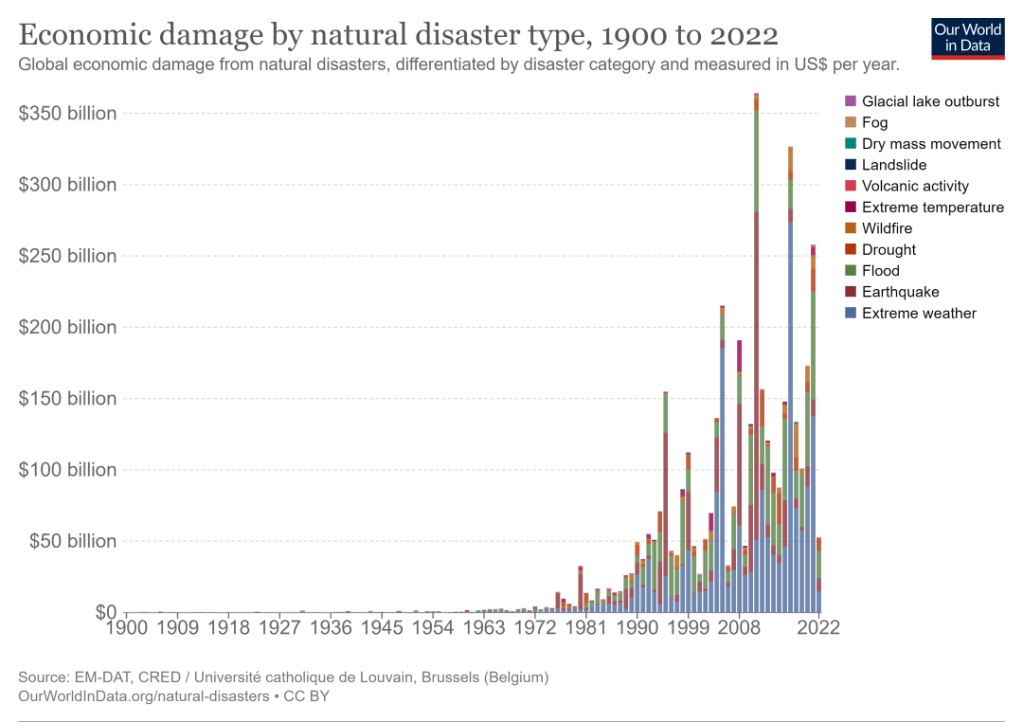

According to the chart from Our World in Data, economic damage from natural disasters has not only been rising since the start of this millennium, it is dominated by extreme weather conditions, which we don’t usually consider a natural disaster. If you look at the economic damage each year – excluding years with a natural disaster of epic proportions – the quiet but most damaging contributor is extreme weather conditions. And considering extreme weather conditions are likely to be regular features of climate the world over, how should the world plan to control food price inflation in the future. Already volatile, it is likely to become even more entrenched at higher levels in the years to come. Will more governments be forced to intervene in agricultural produce markets and set their pricing and distribution? Will trade in agricultural produce – a huge part of world trade – shrink as countries prioritise their own domestic market over international markets? Will agricultural commodity producing countries suffer massive setbacks, and how can they overcome them?

These are some of the questions that ought to be engaging the minds of economists, policymakers, governments, multilateral institutions and the like. Thus far, the world has looked at climate change mainly through carbon emissions and other greenhouse gases, which are mostly focused on energy production and consumption. And while we have made good progress in some countries in the area of renewables and their growing contribution to energy requirements, fossil fuels still do command a large share of world energy production and consumption. The economics of renewables is what turned the tide, attracting huge amounts of public and private investment in recent years.

Perhaps it’s time to turn our attention in an equally focused way to modernizing agriculture in ways that it can withstand climate change and also avoid its disastrous effects. Perhaps the world needs another green revolution, the kind that India benefitted from in the 1960s. More research in developing new and sturdier agricultural crops is required, including using biotech in food production. What about turning open fields into giant enclosed greenhouses, where crops can be grown in controlled temperature and climate conditions? Some of this is already taking place in Europe and in the US, according to this article in the Forbes, which I don’t usually read. Meanwhile, companies in the Middle East are experimenting with vertical food cultivation, one reads through World Economic Forum. I think many such ideas might also tackle other environmental issues such as improved water management and use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides, etc. more effectively. Maybe it’s time to scale up such ideas and see how they can become commercially viable.

The equally big development challenge then, is securing the future of millions of people whose very livelihood depends on the land. Training them to grow food in completely new ways would become necessary, which is worth considering in terms of helping farmers save costs as well as their health and lives. All this might require fewer people to till the land eventually, so that millions can find other more promising occupations. And those who choose to stay farmers will do so out of choice because they are innovating and building good businesses out of it.

Climate change will also impact the insurance industry hugely in the years to come. Agricultural and crop insurance will have to be rethought, in light of the kinds of natural disasters and extreme weather events that are expected in the future and their alarming frequency. Reinsurance too, would have to be innovated upon.

Yet another huge development challenge of the future is climate migration. It is being estimated by climate change and economic experts that millions of the poor and vulnerable – especially those who live off the land – will be forced out of their homes and turned into migrants. This is not a new phenomenon. After all the earth has witnessed ages of nomadic tribes moving from place to place, in search of food, shelter and better climatic conditions. Even now, India has nomadic tribes in the mountainous regions of North India who come down to the valleys and the plains during winter months, before returning to their mountain pastures and local trades the rest of the year. However, what we are talking about is migration forced upon the people, by extreme weather events and conditions. Huge humanitarian disasters caused by natural calamities that drive people out in droves.

This poses yet another huge economic challenge to policymakers and governments, because it could undo decades of good work in reducing poverty, improving health and education outcomes, as well as enhancing employment opportunities. When millions are forcibly turned into nomads, it goes against the very idea of modern civilisation. Until now, the world was trying to cope with the effects of urbanisation, which saw the movement of large populations in one direction – from the rural to the urban. It was seen as edifying what we have always known about ancient civilisations: that people in agricultural societies settle in one place, grow their food and build their lives. If people cannot settle anywhere for long, what can they possibly do to earn their living, educate themselves and look after their health? It would be equivalent to turning the clock back not in decades but in centuries and possibly even in millennia.

The world needs to urgently turn its attention to this climate change catastrophe and build defences against it well in advance. In my opinion, the fight against climate change has to go beyond carbon emission reduction and the energy industry to tackling its effect on the poor and economically vulnerable. What’s more, the fight against natural disasters has been in the area of better preparedness and protecting the poor through early warning systems and financial safety nets which help them tide over the disaster period, as this overview from World Bank shows.

There is very little being done in terms of mitigating the effects of natural disasters or preventing natural disasters from destroying livelihoods of the poor. By which I mean climate change policy that tackles agriculture which feeds billions around the world and is about sustenance and survival for the poor. Agriculture is also directly linked to land-use. There are many challenges that have arisen in recent years in terms of fulfilling competing demands on the land and on people’s livelihoods. These land-use issues are also connected with the environment and with food inflation. There is invariably a trade-off between the choices that policymakers are always faced with. Land for bio-fuels, or for food cultivation? Land for forestry, or for food exports? And more of the kind.

Unless we innovate our way out of this crisis as well, the world will be faced with a natural, economic and humanitarian catastrophe soon. Bio-tech in food production, GM foods, vertical farming, greenhouse farms, etc. are all ideas that will have to be considered in the near future. And as I said earlier, enclosed greenhouse farming might actually deliver other benefits such as lower water consumption and less use of fertilisers and pesticides.

From an environmental point of view, less meat consumption too is good, both for our health as well as the planet. Plant-based meat is already catching on as an idea, but has yet to go mainstream across the world. It allows for more food cultivation for human consumption. And considering that population growth is still a problem in large parts of the world, especially in poor and developing African countries, the world still needs to grow more food so there is enough for everyone.

More ideas, innovation and investments are needed to tackle this next big challenge of climate change. A country like Israel has already innovated a great deal in new technologies in agriculture and in water management. Being a small country, with little arable land, it has been compelled to innovate in these areas. Perhaps more countries around the world – including those with large land mass, such as the US, Russia, China, Brazil and perhaps even India – need to adopt an Israel-like mindset and put their minds to work in these areas.

The world has a laser-focus on controlling consumer price inflation at the moment, as we still cope with the post-pandemic effects. But we are far from controlling the kind of food inflation that is fuelled by wars, like the one on in Ukraine right now. And still farther from tackling food shortages and inflation that is likely to hit us when so much of the earth’s land mass is either under a deluge, or raging in wildfires.

Sounds apocalyptic, I know. And I don’t in the least mean to sound alarmist. But looking around me, and reading and listening to the news from India and from distant parts of the world, I can’t help thinking that we ought to devise better solutions against the next big economic catastrophe. Okay, perhaps the crisis is not tomorrow, but it’s not too distant in the future either.

After a financial crisis and a pandemic, what defences are we left with now, except our inventiveness and our money power. Through both the earlier crises, the wealthy have accumulated even more wealth. Time to put it to better use now.

The featured image at the start of this post is of bushfires in Tasmania, Australia, in 2021, by Matt Palmer on Unsplash