We’re nearing the end of 2023, and it appears that most economies have managed to stave off a recession, except Germany, Austria, Poland and Sweden among advanced economies that might still close the year a little in the cold. Ireland too looks surprisingly weak in 2023, but not if you consider the previous two years of double-digit economic growth that the country has had, according to the OECD.

The rest of the world has mostly escaped recession so far. It was widely feared that central banks’ interest rate increases and soaring inflation might actually tip many economies, especially those in the developed world into stagflation or recession. That said, let us not get too optimistic and get ahead of ourselves. Economic slowdown is still with us and so are the concerns of stagflation in many countries, depending on how long consumer price inflation stays high.

The other fear related to higher commodity prices owing to China’s rebounding in the second half of the year has largely been allayed. The world’s second largest economy is managing to grow, albeit at a much slower pace than previously thought, and is expected to close the year with real GDP growth of above 5% according to The Economist Chart of economic and financial indicators. Consumer prices are still in deflationary territory and the Chinese government is said to have announced a 1 trillion Yuan stimulus, after interest rate cuts, but one hopes it doesn’t all go towards propping up the real estate sector, which is turning out to be a bane for the economy after providing boom in growth rates in previous decades. That’s because real estate is a disproportionately large sector of the Chinese economy, as I wrote in an Owleye column two years ago, and unless they correct this anomaly the problems will persist. Details on how this fiscal stimulus will be used is yet unclear, and I think that the Chinese government ought to encourage private sector investment and growth, after the crackdown on them that has dampened investor sentiment.

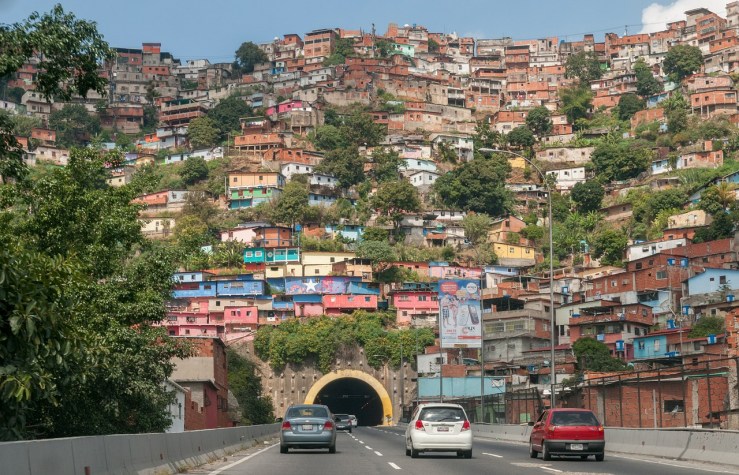

While commodity prices have not spiked on account of China’s return to faster growth – and that’s a good thing – it seems to be taking a toll on many economies in Latin America that are dependent on commodity exports to China. Speaking of high inflation as well, many of these economies from Argentina to Colombia and Peru seem to be suffering both high inflation and high interest rates, with limited prospects for growth, which is a recipe for stagflation and recession. Many of these economies are expected to experience economic contraction in 2023, and who knows what next year has in store for them. Brazil and Mexico seem to be the ones bucking the trend, thanks to a larger domestic economy and trade with the US, respectively.

In the US itself, 2024 is expected to be a year of reasonably good economic growth, fuelled by strong labour markets and productivity growth, thanks to innovation, especially of the AI kind. Biden’s big spending plans too will keep supply and demand buoyant, which is of course a worry for inflation. Many economists think inflation will cool, albeit at a slower rate, making it imperative for the US Federal Reserve to keep interest rates higher for longer.

Next year is also a year of elections in many major economies, US, UK and India included. We can therefore expect tax breaks, sops to various sectors, and other goodies of the kind, even though these will put pressure on countries’ vulnerable fiscal and debt positions. The UK government, while the only one to raise taxes immediately after the Covid pandemic in order to fund the large fiscal gap, has already announced tax relief to individuals and companies in the Autumn Statement 2023, that they think will boost spending and investment. The OBR (Office for Budget Responsibility) does expect consumer price inflation to remain elevated and domestic-driven, though they also say – rather counter-intuitively – that higher inflation will lead to a better fiscal position for the government through wages. In Germany, meanwhile, the government’s budget proposal to repurpose unused pandemic emergency funds worth €60 billion towards renewables, chip production and supporting energy-intensive companies was dealt a big blow by the country’s Constitutional Court.

In Asia, economic growth will chug along, but we must remember that many of the Asian economies – especially ASEAN and East Asian ones – are quite dependent on global exports and trade with China. Therefore, they will remain quite vulnerable to the slowdown in global trade, stronger dollar and to geopolitical tensions. Hopefully, with their strong base in high-tech manufacturing and innovation, they will weather the storm. India is expected to be the fastest-growing economy in the region and thanks to its large domestic market, it will manage to overcome global headwinds. However, the problems for India are international commodity prices, especially of oil and gas, as well as the strengthening of the US dollar. That said, the fact that it is likely to be a bright spot in the global economy ought to attract foreign investment and also keep the Indian private sector invested in the Indian economy.

If you ask me, 2024 is the year when India ought to usher in a new industrial policy aimed at boosting the growth of MSMEs, of the kind that I have recently written about on my blog. This way, we will improve our competitiveness at a time of economic weakness and slowdown in most parts of the world. We do have important parliamentary elections next year in India too, but whichever party or political alliance comes to power would do well to seize the day and undertake important reforms aimed at becoming more competitive as an economy. This comes with the caveat that we should not become protectionist in the process; instead, we ought to invite foreign companies and investors to India even as our Indian companies compete and grow.

Africa is the continent that the world ought to be most concerned about in 2024. It promised so much hope even a few years ago in terms of democracy taking root in countries long impoverished by dictators and despots. Unfortunately, while parts of the continent have grown economically, several countries have fallen into internal conflicts and even war. The developed world as well as democracies elsewhere ought to help these countries end their conflicts and focus on economic growth, else countries such as Russia, China and other autocracies step into the vacuum as they already seem to be doing and increasing their political influence as well as taking advantage of the continent’s rich mineral resources. Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to see economic growth slump to 2.5% in 2023, with Sudan’s economy alone contracting as much as -12%, according to a World Bank Report cited in this Reuters article. Sub-Saharan Africa is also one of the world’s most indebted economic regions, with the ratio of interest payments to revenue having doubled since the 2010s and is now at levels four times that in developed countries, according to the IMF.

Speaking of debt, the entire world has run up huge debt in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic as well as massive fiscal deficits. While countries are trying to reduce their fiscal deficits as a percentage of GDP, either by cutting spending or by increasing tax revenue, they need to calibrate this carefully since they are also in the midst of fighting inflation with the cost of capital rising. Debt – both government and private – is at unprecedented levels already and economies need to manage repayment and refinancing carefully as well. According to this CNBC article which cites a report of the IIF (International Institute of Finance) that is also worth reading, total stock of global debt rose by another US $ 10 trillion in the first half of 2023, taking it to a record high of US $ 307 trillion by Q3 of 2023.

It would be good to know how much of this debt pile is coming due for repayment in 2024 and in which countries, but I couldn’t find this information online. Not even on IMF’s site. I would imagine that with the largest debt piles in the world as percentage of GDP, US, China, Japan and Italy would top the list, not to mention troubled economies such as Argentina and Turkey that have vulnerable external debt positions. In the US, after years of good job creation there is every possibility that US companies having to repay or refinance large corporate debts will now look to accelerate technology adoption and axe jobs. And with AI adoption already apace, this trend might endure for longer putting pressure on individuals and households.

The other fear is that high household debt, with borrowing costs rising in the past couple of years, consumers too might cut back on their purchases, putting downward pressure on consumption demand. While some of this is indeed required in order to cool inflation faster, no one wants it to hurt economic growth which can happen when consumers and businesses cut back on spending and investment at around the same time.

And finally, the impact of geopolitical tensions and wars raging in Ukraine and also in the Middle-East on the global economy can never be overstated. With protectionist and restrictive trade and investment policies, countries might do themselves more harm than good. Commodity prices will tend to stay volatile even through a year of slowdown, and vulnerable economies such as those in Africa will continue to be hit by food shortages, hugely dependent as they are on wheat imports from Ukraine.

I think it would serve us well to expect a further slowing down in 2024, but hopefully not a complete halt or a contraction. All the years of positive and negative base effects issuing from the Covid-19 pandemic will pass next year, and we should see the normalisation of economic activity and growth rates from then on.

Unfortunately, the high fiscal deficits and debts will be with us for a long time after. But at least 2024 can be looked upon as the year the pandemic pains end, and economies focus on restoring their public finances. Companies and people can hopefully look forward to less volatility in their lives and more stable growth starting 2025, if all goes well next year.