It’s June 2023 and the third summer after Covid lockdowns were relaxed in most parts of the world, and when economies began emerging out of the pandemic crisis. It’s also the third year, therefore, of anomalies in economic data correcting themselves, thanks to base effects both positive and negative tapering off. They haven’t entirely disappeared, though, which is why 2023 is still tipped to be a year of global economic slowdown.

That said, let us take a look at how major economies and regions around the world are faring and how they are recovering from the post-pandemic effects. I have written before on inflation being the biggest problem facing many economies, and why. In this piece, therefore, I’d like to focus on how countries are managing to control inflation while still trying to grow their economies. It does look like there are different scenarios playing out in different parts of the world.

The slowing down and recessionary western world

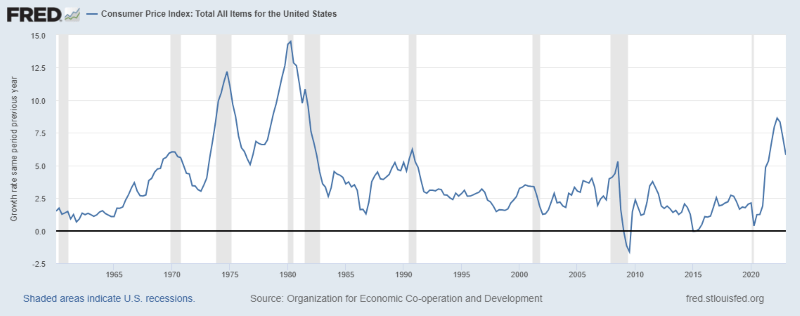

Most of the advanced economies of the West appear to be still focused on battling inflation as it rages, thanks to strong demand conditions still persisting after the Covid-era relief and stimulus measures. With supply chain issues also improving, consumption demand has remained resilient in these economies. There is also a reduction in unemployment and good job creation, especially in the US, which is keeping inflation high. The US economy is responding to the interest rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve, though, and CPI has fallen from the highs of above 8% in 2022, to 4% in the May CPI reading issued most recently, as you can see in the chart below, from the US Fred website. Core CPI in the US is slightly higher at 5.3%, though that too is trending down. All this, while the economy grew by 1.6% in real terms over the previous year in the March 2023 quarter. Giving the US Federal Reserve enough confidence perhaps, to skip a rate hike this time.

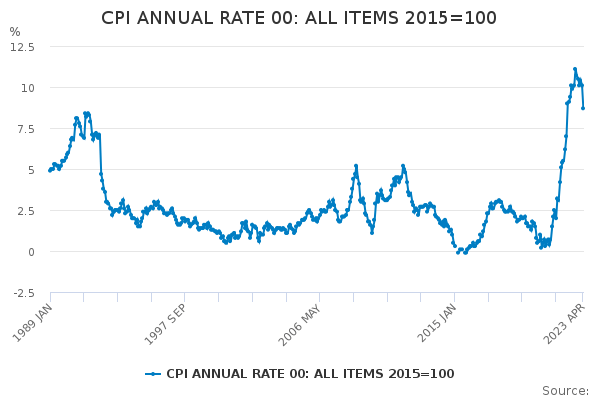

The UK managed to only eke out growth of 0.2% in the March 2023 quarter over the previous year, just enough to avoid a technical recession, and that’s where consumer price inflation is raging the highest at 8.7% in April 2023, lower than the UK highs of well over 10% in previous months, as can be seen in the chart above from the ONS (Office for National Statistics) website. What’s more, despite food prices coming down globally, UK seems to be suffering from unusually high food inflation, at over 19%. The other problem that Britain seems to be suffering from is higher wage increases, and the Bank of England has warned that this is leading to a wage-price spiral, making its job of tackling inflation more arduous. I wondered if both the food inflation and the high wage pressures are not being caused by Brexit, or at least being aggravated by it. I then came across an article citing a study done by LSE, pointing to Brexit indeed, as the cause of high food inflation. That wage pressures would be higher also thanks to the government striking pay increase deals with various unions in recent months is something, I had envisaged and written about.

In continental Europe, the Eurozone managed to grow by 1.0% in the March quarter of this year, though inflation for the region at 6.1% is still a problem. The southern economies of Spain and Italy performed much better, and I suspect it is because of the strong recovery in the services sector, given how dependent they are on tourism especially. However, the unemployment levels in southern European countries such as Spain and Greece continue to be very high. Germany has entered a technical recession, and consumer inflation continues to be high, driven by high energy prices. France has managed to grow by 0.9% with consumer price inflation once again on the high side. The ECB has been hiking rates albeit at a slower pace, and has done so once again.

The chugging-along, export-dependent Asian economies

Thanks to the more virulent Delta wave of the coronavirus that affected many Asian countries, especially those in the East, their economies returning to business took longer. Which is why there was that huge supply shortage of semiconductors particularly, among other electronics goods, that affected the entire world. The world’s largest hub of semiconductor and consumer electronics manufacturing resides in East Asia and China, which has now slowly returned to normal.

Most Asian economies from South Asia to those in the far east are growing reasonably well, under the circumstances. Sri Lanka and Pakistan are exceptions to this, of course, plagued as they are with their own set of peculiar economic and political problems, as is Afghanistan, which is still reported to be suffering from acute food and other shortages as well as oppressive Taliban rule.

Inflation is a problem in south and east Asian countries, though not nearly as bad as that in the western advanced economies. However, most south-east and east Asian countries suffer from a problem particular to the region, which is that they are mostly small economies, and therefore, hugely dependent on exports, mostly of goods. China, India and Indonesia, to a lesser extent, have large domestic markets to cater to, but the rest of the region depends on manufacturing for exports, and are part of global supply chains. Given that there is a global economic slowdown, with the possibility of a recession in some countries, these Asian economies are vulnerable to shifts in global trade and currencies. Which perhaps explains low GDP growth rates in South Korea and Singapore, and significant contraction in Taiwan. That said, they will probably have to consider diversifying their exports and trade to a much wider set of markets so that the western slowdown doesn’t hit them too hard.

Japan too is part of this set of east Asian economies vulnerable to a global trade slowdown. That said, it is quite remarkable that for the first time in many decades, Japan is actually seeing inflation of as much as 3.5%. The Bank of Japan in its latest monetary policy review decided to maintain an accommodative stance. Japan’s March 2023 quarter GDP grew by an upwardly revised 2.7% thanks to increased business spending, while consumption grew by 0.5%. The increased business spending is said to be mostly inventories, so it could well be a one-quarter surprise. One doesn’t know if inflation will sustain for long, either, since consumption is not growing that significantly and exports will remain muted. I think it’s perhaps time for Japan to increase wages – which it apparently hasn’t done in decades since Japanese businesses are averse to raising salaries – so that it might help boost domestic consumption a little more, as this article from the IMF seems to also suggest. And perhaps a saving grace is that Japanese exports are mostly automobiles – including EVs – and consumer electronics as well as semiconductors, which ought to stay steady even during the slowdown. That said, the Japanese yen has weakened the most against the dollar over a long period of time, and this might bloat their import bills, which is perhaps what is also showing up as high inflation.

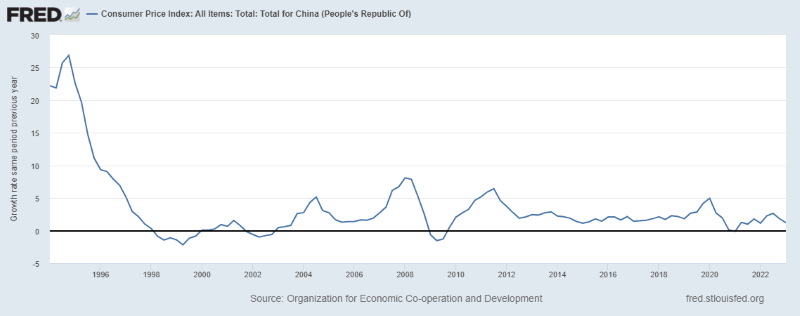

And, of course, all these countries look to China and its market for growth. Unfortunately, the reopening of the Chinese economy has been slow going and the country’s central bank has just announced an interest rate cut in the short-term reverse-repo, in order to boost growth. Further such cuts are expected in one-year and five-year lending rates. In the March 2023 quarter, the country posted a 4.5% growth in real GDP over the previous year, which might slow in the June quarter of 2023. Important economic data for May 2023 released recently suggests that industrial production, retail sales and fixed asset investment all came in below estimates, at 3.5%, 12.7% and 4% growth on the previous year. They didn’t miss estimates by very much, though, and I would say it is still reasonably good growth under the circumstances, unlike the CNBC article calling everything a disappointment. Hopefully, the economy will pick up momentum towards the latter part of the year, and will focus more on its domestic economy, even as it continues to export as part of global supply chains. The country still has a structural problem with its disproportionately large real estate sector, thanks to restrictions in local government being able to raise taxes, and that has a huge bearing on its debt.

India is believed to be a bright spot in all this global economic slowdown, but it too has a fight against consumer price inflation. For the first time in almost three years, headline CPI and core CPI have ticked down slightly for two consecutive months of April and May 2023 and are now at 4.2% and 5.02% respectively. That doesn’t mean inflation is under control, though the RBI has paused rate hikes for now. Meanwhile, the biggest problem in India is high unemployment, which predates the Covid-19 pandemic, though it was certainly aggravated by it. This is because small and medium sized businesses suffered hugely, first under demonetization and then the pandemic and many were forced to either shut down or cut jobs. The peculiarity of small and medium businesses in India is that together, they are the biggest employers, although many of them operate in the informal sector. High unemployment affects Indian economic growth mainly by weakening consumer demand – which is also affected by inflation – and by reducing the government’s capacity to raise adequate income tax revenue. What’s more, the growth in gross fixed capital formation has mainly come from government spending on infrastructure projects.

Inflationary and indebted Latin America

Economic growth is slightly slower in Latin American countries, but given that they are largely commodity exporting countries that depend on the west and on China, these countries aren’t doing badly under the circumstances. Of course, there are the odd problems with economies like Venezuela and Argentina that are age-old and don’t seem to be able to reform soon enough. For the greater part of the continent, economic growth is reasonable with the exception of Chile and Peru which contracted 0.6% and 0.4% respectively in the March 2023 quarter. But inflation continues to rage as it has done in many of these countries in years even before the Covid-19 pandemic.

That and their external debt and current account deficits seem to be the main challenges at this time. Many Latin American economies have high government spending, including on social welfare programmes, and they tend to borrow heavily in overseas markets. I don’t wish to raise fears of the late 1990s and 2000, but they do need to keep their fiscal profligacy and debt in check. Besides, many Latin American countries need to invest more in domestic industry and manufacturing, which could be beneficial to the entire continent, with the several trade blocs and associations that the region boasts of.

Stalling, fund-starved Africa

When many African countries were overthrowing their old despotic rulers a few years ago, I wrote on my blog that this is a good sign for the entire continent. However, those change of regimes didn’t take place as intended by the people, and in countries such as Sudan, it has led to military rule.

On the economic front, I wrote two years ago that African countries too must diversify their economies away from commodity exports and build manufacturing capabilities. The Covid-19 pandemic hit most African countries quite hard, with many of them not receiving enough vaccines, and also not equipped with the health infrastructure to carry out mass vaccination drives.

According to the IMF Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa issued in April 2023, it appears that the region is stalling in economic growth this year, and mainly on account of inadequate funding. Multilateral aid had been cut to Africa as part of Trump’s policy, but this recent lack of funding has more to do with the tightening of monetary policy around the world. This has definitely increased the costs of servicing their debt, as the dollar continues to strengthen, piling on the pressure on poor, developing economies in the region.

Inflation is said to be in double digits in most of the Sub-Saharan countries, on account of the war in Ukraine most probably, followed by reliance on imports and other supply shortages.

One hopes that multilateral financial institutions and development banks will come to the region’s assistance and see them through this crisis.

That said, even with the slowdown in western economies led by the US, the US dollar has continued to strengthen adding to the pressure on countries around the world. To be able to pay for their imports and repay their debts. The effect on the poorer, more economically vulnerable countries is obviously worse. There are at least two ways that countries can make it easier and more tolerable for each other to continue to do business, even amid this slowdown: i) keep trade channels open and avoid protectionism and ii) show greater willingness to cooperate as well as greater forbearance towards debt, especially of poor and developing countries.

The featured image at the start of this post is of a protest in Liestal, Switzerland, during the Covid-19 pandemic, by Kajetan Sumila on Unsplash