As has become commonplace these years, 2023 too has been a year of extreme weather conditions, natural disasters, excessive and unseasonal rainfall in some places, drought in other places. We know that extreme weather conditions and natural calamities are becoming the rule, but it doesn’t conform to any pattern and we are unable to mitigate it.

Thankfully, climate change has moved to the centre in recent years, from being a peripheral issue earlier. And the world has made some progress in reducing carbon emissions as well as preventing global warming from becoming any more extreme than it already has. But all of us would agree, too little has been done. And before it’s too late, we need to work together and concentrate our minds on how to save ourselves and our livelihoods, as well as secure the lives of future generations.

As I had written about the COP26 summit that took place in Glasgow in 2021, the focus was on lowering carbon emissions and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Then, during COP27 in Egypt last year, the focus shifted to climate finance and transfer of technology, which have been the main sticking points in developing countries being able to adopt climate change policies. This year, at COP28 in Dubai, there doesn’t seem to be a theme or focus yet, from what I see on their website. Perhaps, the conference will discuss several issues that are critical to mitigating climate change.

I don’t think the subjects of climate finance and transfer of technology on affordable terms can be ignored; in fact, they ought to be front and centre in the discussions at COP28 and beyond, because so much of climate change policy-making and implementation hinges on these issues. That said, in each country or region the climate change policy priorities might be different, to the extent of the energy-intensity of their economies as well as their economic growth and development agendas, even though more countries ought to adopt growth agendas that are also climate and environment-friendly to start with.

In this respect, we know that western, industrialised countries have caused the most environmental harm over centuries, historically speaking. That doesn’t mean that developing and emerging economies follow in their path; the experience of western, advanced nations ought to be a cautionary tale for the rest of us. And the solution to look for is always the one that balances economic growth and development with long-term environment conservation.

However, we are not even talking conservation right now. The world is so far gone that, backs to the wall, we are looking for policies that will at least mitigate climate change risks in the short term. And even here, I find that the commitments made in the Paris Climate Accord of 2015, are not sufficient to prevent climate catastrophe. What ought to be the way forward in devising and implementing climate change policies?

I think it is a question of priorities and trade-offs, that are made in the interests of the environment. If we are keen on minimizing climate change risks in the short term, we had better be willing to err on the side of caution than barrel on with bravado and foolhardy decisions. I think every new project that comes up, whether industrial or manufacturing or infrastructure ought to have climate change and the environment fully factored into the decision, the costs, the lending and the commitment of the company to protect the surrounding environment. I am certain that under such strict criteria, most projects will be forced to consider a better location, a cleaner technology, and a commitment to keep pollution of all kinds (air, water, and soil) low. This, along with a carbon tax, should help mitigate climate change to a considerable extent.

However, since the world has been so reluctant to impose a carbon tax on businesses thanks to our politicians, we are having to make do with less efficient mechanisms such as emissions trading, carbon import tariffs (as in EU’s CBAM which takes effect this month), ESG reporting (which has instead become an asset class for investors) and the like, and we still can’t find ways to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels.

Instead, if we adopted a priorities and capabilities approach at an economy level, we could identify our climate change priorities – in line with our growth and development priorities – and devise policies accordingly. In terms of what is required to implement those policies, we ought to then see what capabilities an economy has within (research, innovations in new clean tech, financing, etc) and what we need to import from outside. It shouldn’t surprise us to know that the biggest source of carbon emissions in the developed world is from industry and transport, while in poor and developing countries, it is from mining, small, dirty, tin-shed kind of manufacturing and open charcoal/woodfire cooking. The last one about cooking surprised me as well when I read about this years ago, but apparently it is rampant in many African countries. I also know how long it has taken my country, India, to shift from subsidized LPG for the middle classes to making it widely available to the poor in all rural areas. Besides the carbon emissions problem, this kind of cooking also takes a toll on people’s health, especially women.

In this context, I looked at the Green Deal climate policies being pursued by some of the developed countries. While the Green New Deal programme that was initially put forward by the progressives within the Democratic Party in the US was ambitious, it was also unrealistic and impractical. Most of it seems to have been set aside, in favour of policies that form the current US IRA bill, the bipartisan infrastructure bill as well as the CHIPS Act, all of which have an element of encouraging the transition to clean energy. In the EU, on the other hand, the focus of their Green Deal appears to be on energy security as well as net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. The war in Ukraine has made the energy crisis a live and burning issue for the entire continent and the EU has been forced to find alternate sources of gas for heating especially during the winter months. It is not so much of an issue in the US, as it is abundant – though not fully self-sufficient yet – in its fossil fuel supply. Europe has had a much longer history of strict environmental regulations and its ETS too has been around for almost two decades. On CBAM, I have already shared my thoughts in a previous blog post and I hope it can someday be tweaked to form a more efficient and effective global policy in sharing the emission reduction burden between countries, at least of the G20.

While both the US and the EU have made significant progress in shifting to renewables, more needs to be done in the area of developing clean technology. And I don’t mean only EV batteries and the like, but more fundamental industrial and manufacturing technology. I am not sure how much progress the world has made in the underlying manufacturing technologies becoming cleaner, and more energy-efficient say, from the 1960s onwards, especially in core industries that also happen to be the most polluting, eg metals, chemicals, cement, oil and gas, power, etc. There is still clearly a need for more clean technology to be developed. Here, the US seems to be providing for more research in clean technologies, while the EU Green Deal doesn’t address it at all.

Reading a policy brief from Bruegel on the governance framework for the EU Green Deal, one realizes the problems in finding agreement between EU member countries. It says that while climate change policies are decided at the EU level, energy is a national subject and each country is free to pursue its own energy policies. This becomes an even bigger problem, when you consider how central energy is to Europe’s climate change policies, focused as it is on energy security as well as lowering carbon emissions.

I was wondering if the EU couldn’t push the envelope further and also get around the problem of energy being a country-specific issue, by focusing on innovation. As I write this, I also realise that the EU discourages and disallows state subsidies to be used to benefit any particular business or company, which means it closes the door on incentivizing innovation. I think this must change and the EU ought to find a way to boost research and innovation in new, clean technologies both within its academic institutions and universities as well as through companies. This will not merely provide EU countries access to better and more effective solutions to climate change over the long-term, it will also make the EU more competitive in this area, when compared with the US, China and Japan.

Of course, it is entirely possible that the US federal government is incentivizing research and development in clean tech, environment-friendly products and ideas because it doesn’t have any measure to keep carbon emissions in check. Whereas, in the EU it is perhaps the prevailing wisdom that their ETS will itself force companies and businesses to switch to cleaner technologies and lower pollution. I still maintain, though, that shifting to clean technology, and producing clean technology are two very different things: in the latter, you achieve the former and also become more competitive.

In this area, another developed and industrialised country, Japan, could also raise its investment and innovations in clean technology in the future. Japan has pledged to reduce its carbon emissions by 46% from 2013 levels by 2030 and, like the EU, has committed to becoming net zero-carbon by 2050. When you consider that the country was forced to go off nuclear energy for many years after the Fukushima disaster and was importing huge amounts of fossil fuel, especially LNG as a result, this NDC commitment from Japan is really commendable. There are certain specific measures that the country is also taking, according to the World Economic Forum. As an industrialised nation that has huge capacity in technological innovation and access to a technically proficient workforce, I think Japan can stretch its capabilities in inventing and producing green technology across many sectors.

For the global effort in lowering carbon emissions to even become meaningful in real terms, China has to step up to the plate and do its bit. In recent decades, the country has become the world’s biggest emitter – with India following close behind – but it also has the capabilities and the capacity to pull its weight domestically and clean up its energy sources and usage. China’s NDC pledges to peak carbon emissions by 2030, and become carbon neutral by 2060. China has made huge investments within the mainland in renewable energy – both solar and wind – and has also committed to not building any new thermal power plants overseas. The country is said to have renewables capacity already at 50% of total energy capacity and is ahead of schedule in meeting its renewable energy commitments, which means its carbon emissions might peak even before 2030. However, coal usage is still massive at 52.9% and they need to do more in terms of energy transition. Let’s not forget China is the world leader in solar panels, EV production and battery technology, though their primary source of power might still be coal!

This is rather similar to India, except that we have begun our EV journey only a year or two ago. And our main source of power is still thermal, which doesn’t say much for our transition to electric mobility. I have already written about India’s NDC pledge in a previous blog post and believe our reduction of carbon emissions commitment to be a feeble one. One hopes that our pledge to reduce the emissions intensity of our GDP by 45% by 2030 can be met, but I am unable to see how we can achieve this unless we reduce our dependence on coal and other fossil fuels.

The big shock is from the UK, where Rishi Sunak’s government has rolled back many of their green policies, especially to do with phasing out ICE cars and shifting to EVs by 2030 as earlier committed. The government has also decided to continue to support households on energy consumption and protect them against rising prices. This is understandable since the UK is in election season, but I think the Tories are mistaken if they think that this volte-face will win them more votes next year.

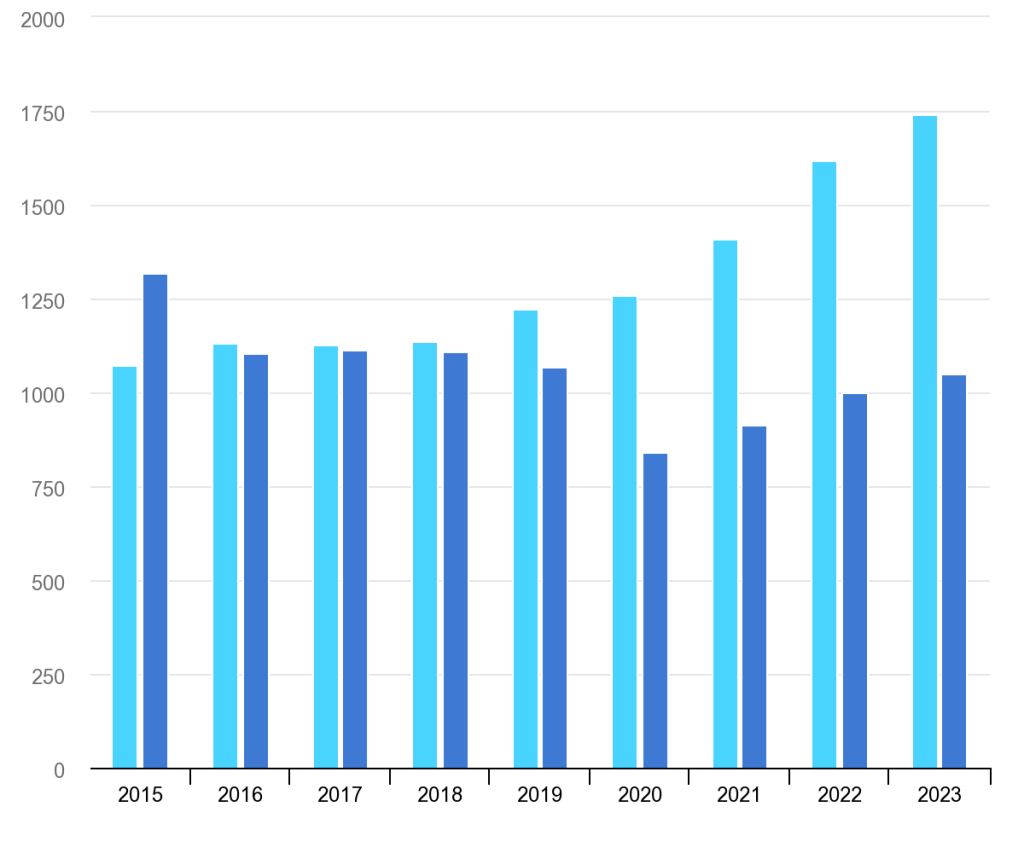

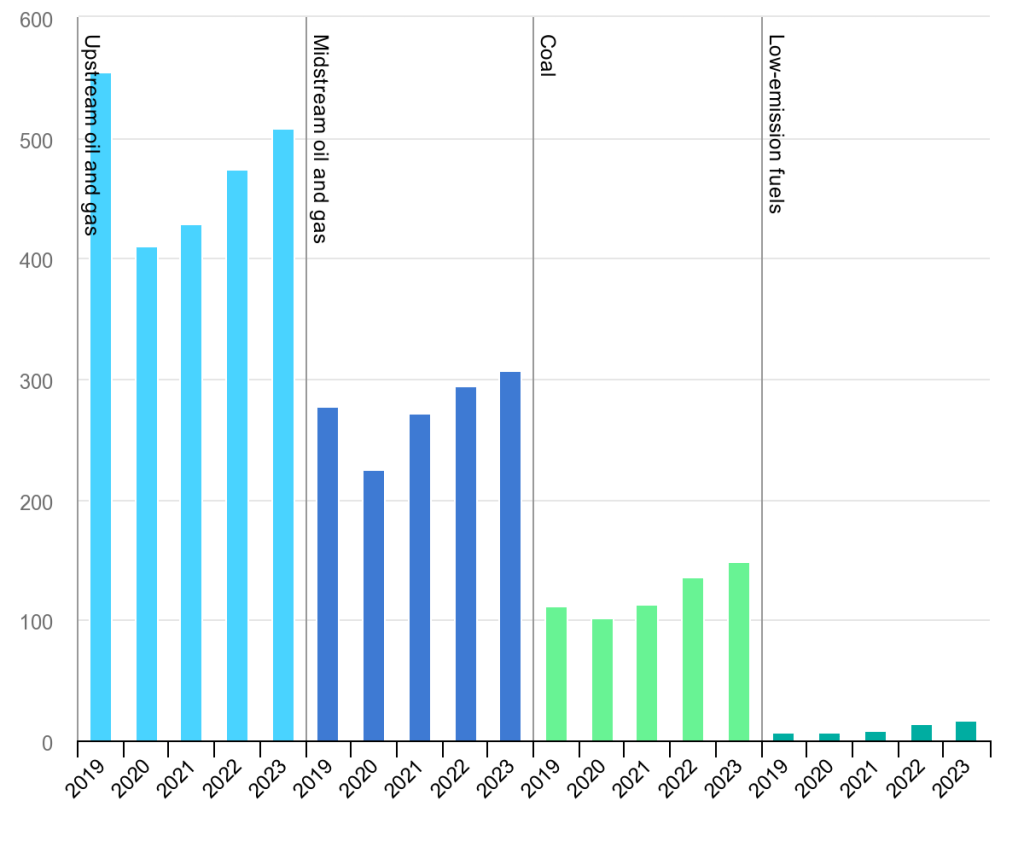

The future of low carbon energy globally depends on many things: ending subsidies for fossil fuels, shifting to renewables, innovating in clean technology and financing transfer of technology on reasonable and attractive terms. Looking at the charts from IEA (International Energy Agency) that I have shared above, you can see where we stand today. Mitigating climate change and its impacts also includes agriculture and the livelihoods of the poor, as I have written more recently. That too is a field open for innovation.

As we head towards COP28 to be held in the heart of the petro-dollar wealthy world, one hopes there will be clear progress and action on climate finance and technological innovation.

The animated owl gif that forms the featured image and title of the Owleye column is by animatedimages.org and I am thankful to them.