Sounds like a crazy statement to make about the world’s largest trading bloc, comprising 400 million people, you may think. But not if you consider the EU’s own aspirations and ambitions, captured in Mario Draghi’s voluminous report. The EU’s own predicament faced with the raging Ukranian conflict with Russia on the one hand, and with Trump’s tariffs on the other, makes it imperative that the European economy focuses on building its economic capacity.

I have written about the European economy from time to time, but I hadn’t delved deeper into the constituents of it as I have done now. The last time I wrote about it, I had written about all the big plans that the European economy was making based on Draghi’s report and I also combined the UK economy with it, in anticipation of what the new Labour government would announce as part of its economic policies. As far as the European economy is concerned, I had written then that Draghi’s report focuses on the need for increased investment in digital technology and AI, and in clean and green tech, as well as the EU’s security and defence preparedness. This was against the backdrop of weak economic growth in EU as well as high inflation at the start of this year.

Now, the economic situation in Europe is much better, with inflation lower at around 2% and with economic growth also better than what was anticipated. The ECB has held interest rates steady once again, and the first estimates of GDP growth suggest that the Eurozone and the EU have grown at an annualised rate of 0.2% and 0.3% respectively. Countries that registered higher growth this quarter are Sweden, Czechia, Portugal, France and Spain, while Germany and Italy stalled. So far this year, corporate earnings for European banks are also better, considering that European banks took a longer while to recover from the Euro crisis in 2012. The health of banks in Europe is important as lending to households and businesses still remains their core and most dominant activity. The European economy managing to grow and tackle inflation despite the US tariffs on European exports to the US is good, though it might have been worse with Trump’s original tariff plan. That said, the latest flash estimates of CPI in October 2025 suggest that inflation in Euro Area is lower sequentially, but on the high side hovering between 3% and 4% in many East European economies. With winter approaching energy costs might be the one to watch in Europe.

However, the effects of the US tariffs are yet to make their full impact known, and the second half of this year and the years ahead will reveal more about their effect on the EU economy. When you think about the EU and its reliance on trade, you realise that so much of EU’s trade is within the regional trading bloc. This is truer of some European countries than others, but it is a sizeable chunk nevertheless. Many have argued for Europe to diversify its trade, as have I on my blog for all countries, including my own, India.

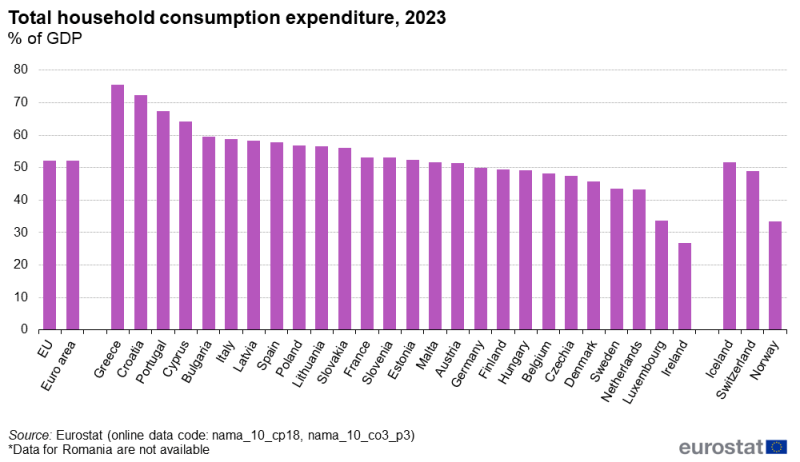

While the EU diversifies its trade with the rest of the world, it also needs to look within for levers of growth it can pull. The domestic economy could provide answers to improving growth on a longer-term basis. On looking at the constituents of EU’s GDP, I discovered that the shares of both private consumption and total investment are quite low. Even when you compare it with India’s economy, these shares look weak and do need to be boosted. The overall share of consumption in EU’s GDP is around 51% and that of total investment is around 21%, both below par, you would have to agree. Of course, this varies between EU countries, though there are many of the larger EU economies that don’t invest enough such as Germany, Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Denmark, Poland and Greece. Incidentally, investment in the UK is the weakest, though it is no longer part of the EU. This low share of investment is true for even the pre-Covid years, and if anything, it seems to have improved slightly during the Covid years for some countries.

As I had written in my previous blog post on the EU economy, investment in EU economies tends to be dominated by private investment to the extent of four-fifths, and government investment is only a fifth of the total investment. This definitely needs to improve, besides raising the total amount of investment (GFCF) in EU economies to around 25%-28% of GDP by 2030 and maintaining it at this level for another decade. I think this is required just to keep the European economies growing at a better pace in the foreseeable future. This does not include the additional technology and innovation specific spending of around €700-800 billion that Draghi has estimated, is required annually, in order to raise the competitiveness of European economies.

In order to institutionalise this level of higher investment required through the next couple of decades, perhaps the EU needs to build it into its annual budgeting exercise. I took a look at the EU budget for 2025 for the first time, and it appears that the revenue side is estimating lower income from customs and import duties, which is their main revenue earner. Perhaps this is in anticipation of weaker trade with the US and slower global trade, but it is clear, therefore, that the EU has to focus elsewhere for economic growth. On the expenditure side, I notice that single-market, digital and innovation – the first account head – is allocated less spending than the cohesion and resilience head, which is allocated the most funds. For some strange reason the cohesion and resilience head funds increase ten-fold between 2021 and 2022, with its subhead economic, social and territorial cohesion increasing thirty-four times in the same period! The other large expenditure head is natural resources and environment which also receives higher funding than single-market, digital and innovation.

I think some of these expenditure priorities need to be rethought in light of the Draghi Competitiveness Report, allocating higher funds to single-market, digital and innovation in the years ahead, and raising its ceiling. Besides, the single-market, digital and innovation area needs to be seen as part of achieving economic cohesion as well, so that the economically and technologically weaker countries can be brought to speed with the rest of the EU. This is what I mean by institutionalizing the investment requirements as part of the budgeting process itself.

The EU Commission President, Ursula Von der Leyen also presented a multi-annual EU budget for 2028-2034 in July, on which Bruegel has shared its views. I tend to agree that the increase in budgetary spending from 1.1% to 1.26% of GNI is paltry and will not help to achieve the levels of economic growth and competitiveness that the EU is aiming for. I think it should be closer to 4% of GNI, if not 5%, if it is to have any effect at all.

Now, shifting our focus to the consumption part of the EU growth story, it is weak at around 51% for the Euro Area and around 52% for EU. Of course, here again there are country-specific variations, but not that significant. If you look at the laggards in consumer spending, these are mostly Northern European countries including Germany as well as Hungary and the Czech Republic, where household spending is around 50% or less as a share of GDP. I have been reading in The Economist and elsewhere for years that Germany is weak on consumption as well as investment (especially on infrastructure), even when it was the largest and strongest economy in Europe. Where is all the large current account surplus accruing to Germany on strong trade, being put to use, one wonders.

Governments of EU countries have to frame policies that boost consumer and household spending as well as investment. Some of this might require lowering VAT rates, as also reconsidering the entire social spending that European governments engage in. With an ageing demographic, European economies need to think long and hard about the policy choices they have to make now, so that economic growth doesn’t stall, and can instead become stronger and more competitive in the years ahead. With high levels of debt and large fiscal deficits, EU economies need to rethink their social spending requirements and pare them down, commensurate with what their state finances can afford. France has just had to ditch their much-touted pension reform in order to save the government, and avoid fresh elections yet again. I read that Nordic economies have been paring down their welfare state gradually over the years, as the need for welfare spending have also reduced, and perhaps one can look to those countries for solutions. These economies had the largest welfare states at one time, and having achieved high levels of prosperity as well as equality of income and wealth, they are in a position to reduce dependence on it.

And when it comes to savings, more needs to be done to encourage European households to invest some of their savings in financial assets that will help improve their wealth, as well as contribute to productive areas of the economy. Speaking of which, the EU plan to unify and integrate their capital markets needs to move ahead at a faster pace, as so much of new investment depends on it. EU economies’ increase in defence spending under the new NATO requirements, as also improving their defence preparedness against Russia, will provide an immediate boost to their economies through investment. Germany’s new medium-term fiscal plan looks to benefit significantly from this, but this shouldn’t be seen as the only way to boost investment and economic growth. There are plenty of areas that need additional and new investment in European economies, from energy and broadband networks to digital technology and AI and cloud infrastructure, that all must be addressed. To conclude this article, I suggest that the EU reduces its overwhelming attention on trade as the only path to economic growth, when trade is likely to be slow and weak for sometime and there are other areas that provide scope for growth. Household consumption and investment, particularly by governments, could provide impetus to future growth as both are below par right now. Welfare spending might need to be pared down gradually and fiscal reforms are needed to keep social spending in check. It is not that trade is not important for the EU, but that it is not the only way to achieve higher growth for longer.

The featured image at the start of this post is of the Hamburg port by Markus Kammerman on Unsplash