At a time when India seems to be scaling new heights at least in GDP rankings globally, there couldn’t have been a timelier book on India and its place in the world than The Golden Road. William Dalrymple’s latest book, The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World attempts to tell the story of how India as a prosperous and vibrant country in ancient times helped spread uniquely Indian ideas, art and culture as well as science around the world. An ambitious project, with a large canvas to explore, you would think, without necessarily having to plumb the usual “civilisational state” trope about India. I had presented The Golden Road to my aged father for his birthday last year, and had the chance to read it only now.

The book thankfully, and I think quite intentionally, avoids this trap and is the better for it. There are so many ways to tell the story of India’s unique influence on the world without having to harp on our ancient civilization alone, especially when they are about ideas, art and culture, religious thought and science that continue to live to this day. The enduring nature of India’s economic, scientific and cultural influence in the western as well as the eastern world is a huge world to explore, full of interesting twists and turns as well as an enduring legacy.

To start with, The Golden Road sets the record straight on how India spread its ideas and influence from the time before Christianity to well after Islam came into being, and how India’s economic, cultural and scientific influence rode the wave of whichever country or culture it came into contact with at any point in time. This, I think is one of the book’s main arguments. That India’s influence or the imprint it left on countries or regions around the world didn’t depend on any particular allyship, but that it grew precisely because it was so broad-based and widespread in its appeal. Dalrymple refers to this as the “Indosphere”, to indicate the extent of India’s influence over much of East Asia, Central Asia and indeed, Europe. In his introduction to the book, he writes of how India was a confident exporter of its own diverse civilization and how most of it spread through trade. He even writes about how Indian traders used the peculiar geographical phenomenon of the Asian monsoon winds to travel both east and west to do trade.

“Every summer, the heating of the Tibetan plateau creates an area of low pressure which sucks in moist, cool winds from the Himalayas to the warm seas beyond. The Indian peninsula sits in the middle of this vortex of winds which blow one way for six months a year, then reverse themselves for the next six…

Early Indian traders used the sea roads of monsoon Asia to travel in two directions. Many headed westwards on the winter winds to the east coast of Africa and the rich kingdoms of Ethiopia. Here, they had a choice. One northern fork led through the Persian Gulf to Iran and Mesopotamia; the other to the south, via Aden, took them through the Red Sea to Egypt.”

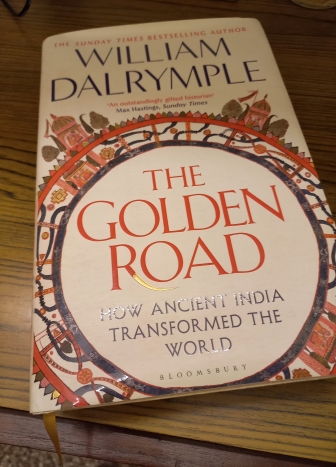

This is not all there is to Indians trading with the world. The book begins with the story of the Ajanta caves and its paintings which depict Buddhist stories, called the Gale of Stillness. Dalrymple then proceeds to tell of how the life of philosopher-king, Siddhartha as well as of Jainism, founded by Mahavira earlier, were a response to the Vedic system of sacrifices, caste system and elaborate rituals. There is a detailed description of the cave paintings, including about the entire enterprise being funded by contributions from local merchant guilds and craftsmen, highlighting the cosmopolitanism of Indian urban society. He also writes about the journey Buddhism travelled from the 5th to the 3rd century BCE, when it left no archaeological traces, as in no inscriptions or text, which I find strange. Naturally, the role of King Ashoka (I thought Ashoka was Emperor, not King), in spreading the word of Buddhism is hugely important here, as he spread the message through his missionaries and famous rock edicts.

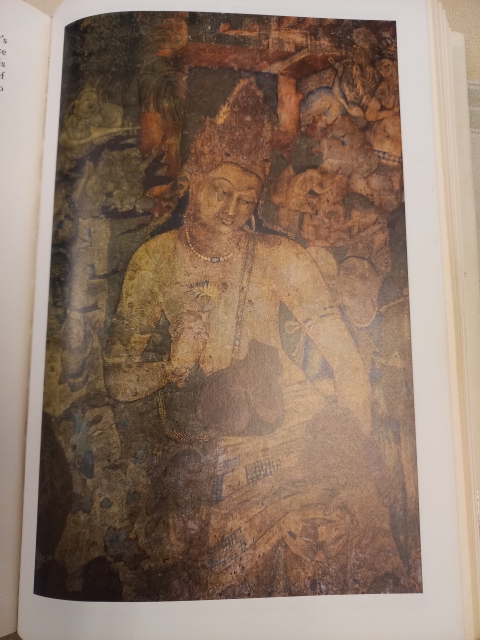

The author also touches upon the influence that foreign arts and culture – particularly Greek and Persian – had on India. This reversed with Buddhism bursting out of India in all directions since Brahminical taboos on seafaring prevented Vedic people and their influence through travel and trade. Even so, the Buddhist art of Gandhara is so clearly influenced by Roman art tradition in its elegant lines and sophistication, according to Dalrymple. He also writes about ancient India’s trade with the Roman Empire, and how it might have drained Rome’s wealth at the time, citing Pliny.

“Whoever owned the ships or worked the ropes, it is certain that the trade between India and Rome grew at speed from the first century as merchants realized the scale of the profits that could be made: Pliny mentions that goods purchased in India could be sold for one hundred times the price in the Roman Empire. It brought massive enrichment to Indian exporters, but at the same time some anxiety to those keeping an eye on the health of the Roman economy. As early as the reign of Nero, there seems to have been a dramatic drain of western gold to India.”

Further, Dalrymple says that “Pliny was equally unimpressed by the gemstones of which he says India was the leading exporter. In his Naturalis Historia he describes India as “the sink of the world’s most precious metals… There is no year which does not drain our empire of at least fifty-five million sesterces.”

There is an entire chapter devoted to the role that the Kushan Empire in the Hindu-Kush region led by King Kanishka, played in spreading Buddhism and its ideas through Central Asia. Dalrymple writes of the Kushans’ interest in urban refinement and in other religions and cultures, which meant giving up their Scythian roots and adopting the settled Hellenism of their Bactrian-Greek predecessors. Until the Kushans opened up access to the Hindu Kush mountains by taking control of the passes, there was no evidence of interaction or influence of Buddhist ideas or the religion in the region. Under Kanishka’s reign and expansion, Buddhism achieved its zenith with the building of the largest Buddhist stupa outside Peshawar and the setting up of the Fourth Buddhist Council in Kashmir.

heavily influenced by Roman art

If Buddhism benefitted from the Kushan Empire in the North, travelling up to Central Asia and later to China and the East, Hindu art and culture also spread eastward through the empires of the Pallavas and the Cholas in South India. However, none of these ideas and influences were ever colonial, by design. This is yet another important argument of Dalrymple’s book, but it is buried under so much intricate detail of kings and empires, art and iconography that it fails to make itself heard. In fact, it is buried in an obscure reference note in the book which any casual reader might easily miss. Not only is this the book’s second most important argument, it could have been the focus or the central argument of The Golden Road. Dalrymple does mention in the reference note that there are historians belonging both to the colonising and non-colonising camp and that he is firmly in the latter. I wish he had spent more time on this particular aspect of the Indosphere, unique as it is from all other countries whose cultures have been imposed on conquered territories and colonies.

India’s influence was truly spreading through its ‘soft power’, well before the expression was even coined by Joseph Nye Jr of Harvard University, who passed on last month. This aspect deserved to be explored in its entirety and established through historical facts. India’s influence both in the west and in the east was brought about through trade, travel, people-people contact with other cultures and through a process of acculturation, assimilation and integration. This is particularly interesting when you compare it with Ancient China’s influence on the world, which Dalrymple does make in the book, but only in passing. I haven’t yet read Peter Frankopan’s The Silk Roads which I do intend to do, but it strikes me that another important area of difference between India’s influence and China’s is that Ancient India’s legacy to the world belongs to the world of ideas, thoughts, religion, art and culture as well as language and scripts, mathematics and science. Whereas Ancient and Medieval China’s influence on the world is more through produced goods, from fine silks and porcelain vases to tea, of course! You could say that although the world has changed between then and now, some things haven’t changed at all!

Speaking of Dalrymple’s treatment of the subject of the spread of Buddhism in China, certain chapters in the book seem to create a misleading perception since they dwell on a particular Chinese scholar, Xuanzang, who came to India to study at Nalanda, the world-famous university of Buddhist teachings and scholarly studies, and his association with a certain Empress Wu Xetian of China who helped spread Buddhist ideas by building monasteries across China. I think these chapters are superfluous as they tend to diminish the importance of the book, with unnecessary details about both the scholar’s and the Empress’s lives. What makes it worse is that the author relies on biographies of both these protagonists in order to write about their contributions to the spread of Buddhism in China, leading the reader to almost think that Buddhism grew in China in the 7th century thanks to them. Besides, I think that referring to the Empress as the fifth concubine and describing her rise to power is all unnecessary distraction from the main subject of the book which is Ancient India’s influence on the world, and it strikes me as unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses’ mischief and meddling in publishing, among other things. Buddhism not leaving any archaeological traces as inscriptions of text from the 5th till the 3rd centuries BCE until Ashoka’s empire, also reeks of the same mischievous idiot bosses.

This, when we all know that Buddhism reached China much earlier in the 1st century, as Dalrymple himself writes in Chapter 4, The Sea of Jewels: Exploring the Library of Nalanda. Having read John Keay’s excellent book on Ancient and Medieval China, titled China: A History, I was aware that Buddhism coexisted in China along with Daoism and Confucianism. In the complex history of China’s warring states, there was also an attempt to unify kingdoms and regions, such as the Qin and Han empires, as well as the Northern Zhou leading to the Sui and the Tang empires. There were times of the return to Confucianism in order to make non-Han rule palatable to the northerners of Zhou, when Buddhism and Daoism were proscribed, as well as the reversal of such policies decades later under Sui Wendi.

John Keay writes in China: A History, “Cultural and commercial contacts between the north and the south had never ceased during the ‘Period of Disunion’, but the social distinctions that so struck the visitor in, say, the fifth century were no longer so clear-cut. The stereotyping of northern rulers as bloodthirsty and uncultured ‘barbarians’ who lived on mutton-and-dumpling stews was as unsustainable as that of southerners as effete and indolent courtiers picking at fish-and-fried-rice delicacies… North and South shared more than they cared to admit. Both segments of the erstwhile empire accorded primacy to devotional Buddhism; both honoured Daoist, Buddhist and Confucian scholarship; both treasured their common linguistic and literary heritage and both still subscribed to the ideal of the ‘Middle Kingdom’ (zhongguo) as a single integrated entity.”

The chapters describing the spread of Hindu religious ideas, beliefs, epic stories and iconography throughout South East Asia during the rule of the Pallavas and the Chola Empire are generally well-researched and well-written. However, there is a reference to Mahendravarman Pallava (571-630 CE), third monarch of the Pallava dynasty in the context of the prolific temple-building that took place in Kanchipuram that he converted from Jainism to Shaivism at the hands of poet-saint Appar, that strikes me as dubious.

It is also in this context, I think that Dalrymple feels the need to explain his view that India’s influence in this region was not of a colonising nature, and I think it might be because the Chola Empire in particular is said to have exercised a much more muscular reign and was also more aggressive in trade with countries in South-East Asia. There are a lot of elaborate and detailed descriptions of Hindu art, architecture and iconography in these chapters as well, but to understand this dimension of Indian influence in the region, Heinrich Zimmer’s The Art of Indian Asia is a much more serious, in-depth and scholarly read.

I think the last couple of chapters in the book on valuable and enduring Indian contributions to the world of mathematics and science could have been given more importance. The fact that Arabic numerals were essentially Indian in origin and the role of the caliphs in Baghdad in translating the book, Sindhind, and disseminating its contents across the Arab world and indeed even in Europe was news to me. I am not sure of the substantiating evidence that Dalrymple provides to bolster his argument, decorated as it is, with details of strange characters, languages and script as well as art and iconography again. The role of Fibonacci in spreading the mystery of the Indian numeric system in Europe and through western civilization is curious as well. Dalrymple seems to think that the game of chess too originated in India, when it is a well-established fact by now that chess is Persian.

In the ultimate analysis, The Golden Road impresses with its vast canvas, its ambition, and the richness of details provided in every page, particularly of empires, religions, language, art and iconography, but fails to convince through the force of its argument. Unfortunately, the reference notes that Dalrymple provides for most of the chapters are either too recent or too obscure and am not even sure exist. This would be surprising if true, since the historian-author would have access to some of the finest libraries in the world for his research. However, I wouldn’t be surprised if unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses at Perfect Relations have meddled here as well, since they have interfered with reference notes in other recent books that I have read – all to cover up their unprofessional nonsense with notes and cash in their circus of an office in Delhi!

As I have already written, there are three main strands of the book’s argument that I could see while reading The Golden Road, but Dalrymple loses them and himself in intricate description and finery, at the expense of history and historical fact. I was never a student of history but have read enough history to know when facts are blurred by art and iconography and reliance on strange references. The couple of reviews of the book I read seemed to focus more on kings and empires as well as legends . Now that I have read The Golden Road, I am not surprised that the reviewers were taken in by the kings, empires and finery. When writing about ancient history, relying on archaeological finds, art and inscriptions of the period is unavoidable I suppose. But when they become the main subject and obscure historical facts, it becomes a problem. The book reads well, since Dalrymple is a fine writer, but as a historian, has he really done the subject enough justice is the question. Western readers might find the subject fascinating, nevertheless.

I am looking forward to reading Peter Frankopan’s The Silk Roads sometime soon. I wonder if there isn’t a new style of history writing that is easier, breezier, and lighter in order to make history popular, that is favoured by historians and publishers alike, nowadays.

In the meantime, my aged father has just gifted me a copy of Sam Dalrymple’s book, Shattered Lands, for my birthday this weekend! Looks as though The Silk Roads will have to wait.