I am reading the second volume of the three-volume selection of Gandhi’s Moral and Political Writings, edited by Raghavan Iyer, that is part of my aged father’s library at home. I had read the first volume decades ago when I was visiting my parents from Delhi and thought it’s high time, I read the remaining volumes. And it is only recently that I also discovered that Raghavan Iyer is Pico Iyer’s father!

Reading more of Gandhi’s writings now, I am inclined to think that cultivating a Gandhi-like mindset at a time of great volatility and change might actually help us cope better with these trying times. It is mere coincidence that my article also happens to go live on India’s 76th Independence Day. A happy coincidence it is too, since nobody had to deal with greater chaos, volatility, uncertainty and change as our freedom-fighters did in the previous century. And perhaps no person knows more about maintaining one’s focus and determination and staying steadfast to one’s goals during such times, as Gandhi once did.

At one level it might seem strange that I should invoke Gandhi when talking of volatility and change in today’s world, led as it is by technology. We all know Gandhi was averse to rapid industrialization, seeing it as an evil of modern civilization. He would rather we focused on our villages, and try and make these self-sufficient units of the larger Indian economy. I had written recently on my blog on how we could achieve a better connection between our rural and urban economies through handicrafts and elevating these to a luxury industry. But that is not what I wish to write about in this piece. I would like to explore aspects of Gandhi’s thinking and certain ideals that strike me as appropriate for today’s VUCA world.

I realise finer nuances of Gandhi’s thinking as I read more of him now. The book is a compilation of many of his own articles and speeches written for publications such as Harijan, Navjivan and Young India, as well as his letters and correspondence with people from India and around the world. Through this, we get a better idea of Gandhi, the man, what motivated him, what he was in search of spiritually and in practice, what made him tick and how he connected with the wider world. We tend to see him as a man of deep contradictions, which he was indeed. But what I realise now is that a lot of what we see as contradictions in Gandhi are actually his ability to see things in their proper context.

You would think that a man so motivated by spirituality and faith could hardly be logical and reasonable in his views and thought processes. In fact, so often in his own letters and writings he talks of the divide between faith and intellect; the former driven by the heart and the latter driven by the mind. However, when you read a lot of his writings which reflect his thought process and his world view, you realise that he has the clarity of thought to be able to assess each idea or problem in a specific context. And it is precisely because Gandhi is able to view each situation or problem in a certain context that he is able to avoid the problems that arise with sweeping generalisations of all kinds. If the context were to change, you can be sure Gandhi’s opinion would change as well. Not just that, he is able to explain his thinking and the why in very clear and lucid terms. Of course, that is also because Gandhi uses language very simply and appropriately, without letting it obscure the meaning of what he intends to communicate, as I wrote recently in my blog post on communicating clearly.

Take Gandhi’s views on the caste system we have in India, which was such an important part of his long-running debate and argument with BR Ambedkar lasting almost their entire lives. In an article that appeared in Young India in January 1926, Gandhi is actually answering three questions put to him by a friend, the first of which is on the caste system:

“Caste as it exists today is no doubt a travesty of the original four-fold division which only defined men’s callings. And this trifling with it has been its undoing. But how can I, for that reason, discard the law of Nature which I see being fulfilled at every step? I know that if I discard it, I would be rid of a lot of trouble. But that would be an idle short-cut. I have declared from the house-tops that a man’s caste is no matter for pride, that no superiority attaches to any of the four divisions… In fact, a Brahmin, to be a Brahmin, should have the qualities of a Kshatriya, a Vaisya and a Sudra plus his own.”

Strangely, he doesn’t use the word varna, which is how the caste system was traditionally described to mean class (not class in the western sense which implies socio-economic hierarchy, but categories or classification). Nevertheless we can see that Gandhi’s reasoning on the issue is so clear that he is acutely aware of how caste is being misused or abused. That is because in his thinking, caste as the four-fold division of society is part of the laws of Nature meant to help in organizing society through men’s callings. It was meant to be this alone, nothing more nor less.

If you consider Gandhi’s idea of ahimsa (non-violence) which is what he is best known for around the world, the path or route of ahimsa is not merely clear in his mind, he is able to articulate it very clearly as well. To Gandhi, ahimsa is not an end, but a means to an end, which in his case was always truth. Satya (truth) which comes from the Sanskrit sat (that which is) was truth to Gandhi in the sense of knowledge of oneself. He used both in developing his non-violent movement in order to win India’s freedom.

“The word satya is derived from sat, which means that which is. Satya is a state of being. Nothing is or exists in reality except Truth. That is why sat or satya is the right name for God.”

However, through so much of the book Gandhi, while explaining to people his idea of ahimsa and satyagraha, recognizes shades of ahimsa and clearly differentiates between them. Whether in the context of Jainism, vegetarianism, social justice, attitude towards animals, and political oppression, Gandhi defends certain kinds of violence under certain circumstances, as being morally right and not in contradiction with his idea of non-violence. This suggests to us that Gandhi was not an absolutist, and was capable of seeing things in their proper context. In fact, he defends his decision to support world wars on the side of the British even while opposing them in India, on the grounds that they were fighting on the right side of the war, and that he was initially a believer in empire. I find Gandhi believing in empire quite strange, though.

“Ahimsa is not the crude thing it has been made to appear. Not to hurt any living thing is no doubt a part of ahimsa. But it is its least expression. The principle of ahimsa is hurt by every evil thought, by undue haste, by lying, by hatred, by wishing ill of anybody. It is also violated by our holding on to what the world needs.”

Another aspect of Gandhi’s approach to problems and issues that emerges from reading this book is his ability to hold several opposing or contradictory thoughts in his head at the same time. This is not to say that he is indecisive or confused. Quite the contrary. Gandhi seems to be doing this, merely to hold any rash decision or judgement in abeyance, while processing several strands of seemingly opposed thoughts simultaneously. This struck me as perhaps another way in which we in the modern world can manage the VUCA environment better.

I wasn’t very surprised at discovering this, because many learned people from the West have observed this as a very peculiarly eastern or oriental characteristic and have expressed inability to quite understand it. It is perhaps the reason why they say that the East is better at dealing with ambiguity. If seen as the opposite of clarity, they might be right. But I think where Gandhi’s thinking comes from is the ability to not preclude or dismiss anything immediately, but to dwell and ponder over it for a while longer to see where the conflicting thoughts lead us. If there is the concept of truth expressed by Sat (that which is, in Sanskrit), there is also the concept of Neti (not this). And even if we can’t arrive at the truth by any direct means, we can through a process of eliminating what it is not, seek the answer we are looking for.

Gandhi himself explains this very simply through the story of the blind men trying to describe an elephant; he says that each of the blind men was right in his own description, and it is only from the entirety of a situation that we arrive at the right answer. He refers to this as anekantavada or the manyness of reality.

“I very much like this doctrine of the manyness of reality. It is this doctrine that has taught me to judge a Mussalman from his own standpoint and a Christian from his. Formerly I used to resent the ignorance of my opponents. Today I can love them because I am gifted with the eye to see myself as others see me and vice versa. I want to take the whole world in the embrace of my love. My anekantavada is the result of the twin doctrine of satya and ahimsa.”

In certain contexts, Gandhi’s response can be most surprising. For example, with all his emphasis on truth, you wouldn’t expect Gandhi to advocate silence in situations that demand truth-telling. But he does advise this in certain situations where, after weighing the consequences of the truth, it is sometimes morally right to stay silent or to refuse to answer a question.

The third aspect of Gandhi’s approach in the pursuit of ahimsa and satyagraha, is that he was not merely a man of ideas, but of action. Ahimsa and the search for truth were not abstract ideas, but were required to be practised regularly. He believed that in practising these rigorously, one is able to detect weaknesses and problem areas which can be improved upon. And these become constant refrains in many of his writings and letters to people: “My life is my message… Be the change you want to see in the world” and others of the kind.

In fact, in volume 1 of this book, Gandhi writes that he never wrote an autobiography, but about his experiments with truth. And that to write a treatise on ahimsa was beyond his powers. However, he thinks that it is possible to turn his idea of ahimsa into a science because it lends itself to such treatment and welcomes efforts in this respect. He even names three people who he thinks are best suited for the task, the first being Vinoba Bhave, but then goes on to say that he is probably not keen on writing shastras, and also why none of them were in a position to undertake such a project.

What I kept thinking about while reading the book is where did Gandhi get the confidence that he was right in pursuing the path of ahimsa to win swaraj, and in his ability to convince millions of Indians to also do so? This is where Gandhi’s soul-force comes into the picture. This is not soul-force as self-confidence, but a deeper spiritual ability that one has to develop. Gandhi explains his idea of soul-force as the opposite of physical force. It is the spirit inside that says I will prevail, no matter the odds. It is therefore, in equal part determination and discipline.

“My faith in non-violence and truth is being strengthened all the more inspite of the increasing number of atom bombs… See what a great difference there is between the two: one is moral and spiritual force, and is motivated by infinite soul-force; the other is a product of physical and artificial power, which is perishable…. When the soul-force awakens, it becomes irresistible and conquers the world. This power is inherent in every human being. But one can succeed only if one tries to realise this ideal in each and every act in one’s life, without being affected by praise or censure.”

Gandhi’s soul-force was so great that he was able to hold his own in the company of political leaders as well as wealthy businessmen and industrialists, alike. His letters to GD Birla and Jamnalal Bajaj are instructive in how to deal with the powerful: he was always grateful for their moral support and financial assistance, but never obsequious or servile to them.

There is also a speech Gandhi made at the Tata Steel Factory in Jamshedpur, and each of these show us a man who truly believed in soul-force and truth. He was a true ascetic, more than the sadhus and sants of today, but never afraid to speak truth to power. That is what must have sustained his efforts while negotiating with the British, including with Winston Churchill.

His belief in human nature also seems to have kept his hopes alive. He was of the view that fundamentally all men are good, it is modern life that leads us astray.

“Men are good. But they are poor victims making themselves miserable under the false belief that they are doing good… The fact is that we are all bound to do what we feel is right. And with me I feel that modern life is not right. The greater the conviction, the bolder my experiments.” (italics Gandhi’s)

On modern civilization being evil, many of us might disagree with Gandhi. But if we look at the state of the world today and what unbridled industrialisation at the cost of the environment and our lives has done to our very existence, we cannot hand on heart, entirely disagree with him either. Besides, there is so much else in Gandhi’s entire approach to problems and to achieving one’s goals, that I think he would have been entirely at ease in today’s VUCA world.

Being nuanced to the extent of being context-specific and circumstance-specific, being able to hold opposing strands of thought and process them without jumping to conclusions, putting into action one’s thoughts and ideas and pursuing them with discipline, developing the soul-force to proceed against all kinds of headwinds, and a fundamental faith in the goodness of man and in humanity. These to me, are ways in which we can better manage the VUCA environment of today and in the future.

If there is one area from where most of the volatility, uncertainty and change is emanating, it is in technological disruption. Without quite dismissing it as an evil of modern civilization but seeing it as innovation for improving our lives, we can nevertheless develop a Gandhian way of thinking and solving problems.

On that happy note, Happy Independence Day to all Indians in India and across the world.

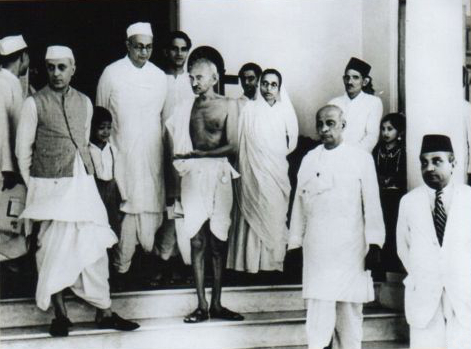

The featured image at the start of this post of Mahatma Gandhi’s statue is by Vikas Rohilla on Unsplash

Post Script: As has become necessary nowadays with almost every book I read – whether new or old, newly bought or old – I share this article with the usual caveat. That this book too – although it has been in my father’s possession for many decades – has been tampered with. For one, it doesn’t have my aged father’s signature on the title page; both my father and I usually sign any new book that we buy and own. My father is more regular with this practice and he usually also writes the name of the town or city where the book was bought, as well as the month and year.

Next, it has the usual tell-tale signs that PR agency idiots along with their cronies in BBDO Chennai might have meddled. I have written about Gandhi writing that he was a participant in wars because he was a believer in Empire, which I find strange. Then, his writing about how it’s not necesssary to answer questions if one wants to avoid lying on moral grounds is equally strange. What is even more strange is that there is a reference to Bertrand Russell in a fox-hunting incident. Where people on the hunt asked Russell if he saw a fox run past and which way it went. Bertrand Russell apparently deliberately lied, sending them in the opposite direction. To this anecdote, Gandhi writes that Russell needn’t have answered at all, and by doing so would have achieved the same effect!

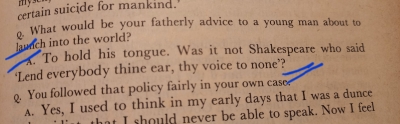

On reading further, I came across bloopers that I am certain Mahatma Gandhi could not have written or uttered, nor could Mr. Raghavan Iyer or the OUP editor have put them there. I am sharing images from the book of passages where Gandhi calls Stalin a great man and that he doesn’t have any data on him, and another section where he quotes Shakespeare as having said something about lending one’s ear but not one’s voice! Both these are in a section on Non-violence and the Atom Bomb dated 1946.

I thought Shakespeare made Mark Antony say something about lending him an ear in his famous speech from Julius Caesar. About lending one’s voice, I leave it to you readers to shed light!

This has to be the worst such offence that the unprofessional idiot bosses from Perfect Relations have indulged in, as far as all their years of meddling in book writing, rewriting, editing and publishing are concerned. My father might have lent these to someone in Goa, who has made it available to these unprofessional PR agency idiots who in turn have had a field day, rewriting, printing and binding it all back together!

As they have indeed also done with my grandfather’s copy of Kipling’s autobiography, which I have written about on my blog. In the case of that one strangely, they have left my grand-dad’s signature intact. After what these unprofessional idiots have done to my collection of books while they were in storage in the packers and movers’ godown in Chennai and while in transit, I am not shocked. But that they have had the temerity to meddle with my aged father’s and grandfather’s books is unconsionable.