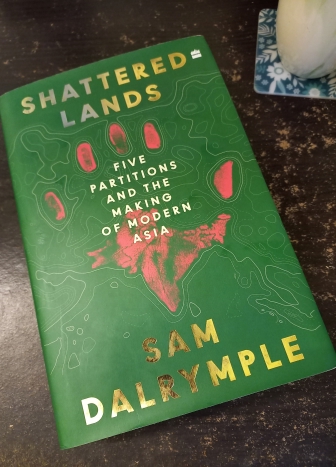

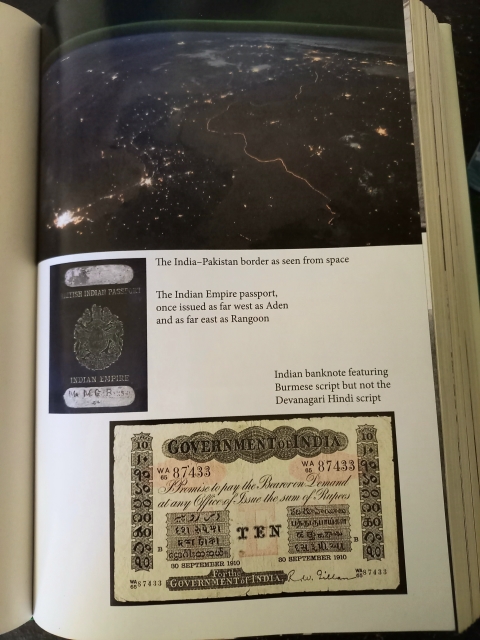

While reading Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and The Making of Modern Asia which my aged father gave me for my birthday this year, I was thinking that this is a book for international readers since the history of India’s partitions has been told many times. But through the first chapter itself, I was surprised to learn about the “Indian Empire”, which is how the British referred to the vast swathes of territory they controlled, from Aden and southern Arabia in the West, to Burma in the East. I thought the word Empire belonged to the British, not to India, since we were the subjects, not the rulers. I was not aware of the Indian Empire extending all the way to the Arabian Gulf, nor of the existence of an “Indian Empire Passport” in the days of the British Raj.

Writing about a message from King George V, the author says,

“… addressing ‘the colonies’ more generally, a message from King George V was specifically directed to ‘the people of India’, who represented four-fifths of the British Empire and quarter of the world’s total population. ‘I reciprocate your earnest hopes,’ the King told his Indian subjects, ‘that 1928 may be the dawn of a new era of peace, happiness and prosperity to you all.’

The ‘India’ he was addressing was almost twice as large as modern India, yet today its scale has been largely forgotten; a few books acknowledge its reach into present-day Yemen, Dubai, Burma or Nepal. Even at the time, Britain played down the size of the Indian Empire for diplomatic reasons, and maps depicting it in its entirety were only published in top secrecy.”

Further, Sam Dalrymple says that “protectorates were all legally part of India under the Interpretation Act of 1889” and were “run by the Indian Political Service, defended by the Indian Army and subservient to the Viceroy of India.” He cites a 2009 article/essay by JM Willis ‘Making Yemen Indian: Rewriting the Boundaries of Imperial Arabia’ in the International Journal of Middle-East Studies.

Since unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses are known to meddle in the publishing of books, I am not sure how much of this was prompted by reading about my visit to a literary café in Paris ages ago, where the waiter asked me if I was from Yemen! These PR agency scoundrels have been doing so much mischief for decades with my career in the advertising industry and my travels.

The book begins with the Simon Commission travelling to India via Aden, that was governed as part of the Bombay province, in 1928. The Commission travel onward to Burma to decide the fate of the country and whether it was indeed part of India. Having annexed Burma, as part of which, Assam and the North-eastern states too became part of India, it is strange that the British were changing their minds so soon as to whether Burma really belonged to India or not. But the author, Sam Dalrymple, doesn’t mention the annexation of Burma by the British anywhere throughout the 400-odd page book, and consequently this episode lacks proper context. In fact, reading the author’s description of how the Simon Commission came to their conclusion regarding Burma, one can’t help but think it flippant and glib.

“By the time the Simon Commission arrived, therefore, the separation of Burma was not yet a given, and it is fully possible to imagine a world in which Burma had remained a part of independent India as its easternmost province. But the Simon Commission had made up their minds before they even arrived and shortly before sailing into Rangoon harbour, Simon had written to his mother, ‘Burma is not really India at all.’”

And about Clement Atlee, Sam Dalrymple writes “Even the letters of Atlee – a liberal and anti-colonial member of the Labour Party – were dominated by casual racism and racial stereotypes. ‘The Burmans are very cheery looking folk – rather Japanese…(but with) an unfortunate propensity to murder,’ he wrote to his brother after a few days in Rangoon.”

Even stranger is Mahatma Gandhi’s visit to Burma and his view that Burma could not be a part of India under Swaraj (self-rule). According to the author, Gandhi arrived at this conclusion because he identified India with the holy land of Bharat from the Mahabharat epic and neither Arabia nor Burma was a part of this. These are cited as references from The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, which I have no way of checking but I find it hard to believe that Gandhi even travelled to Burma and spoke in favour of them seceding.

The author dwells too much on Burma and its internal politics featuring leaders such as U Saw, Ba Maw, Saya San and Ottama, both monks, and Aung San. They appear in cameo roles when Burma’s separation has little to do with them; nor is the author able to do full justice to their lives and political movements. The more crucial aspects of Burma’s separation in my opinion were the invasion and occupation of Burma by the Japanese, at around the same time that the British were planning to give up control of Burma. The roles of the main protagonists are relevant only to the extent that even as Japan attacked Burma, U Saw was seeking help from the Japanese to overthrow the British, whose Burma Governor, Reginal Dorman Smith – who kept a pet monkey – supported U Saw. This must have made for a terribly conflicting and confusing time, politically. Speaking of the political actors in Burma at the time, Sam Dalrymple writes of the US President, FD Roosevelt, writing to Churchill in 1941 a note that is so filled with racial hatred and in such poor taste that you wonder if it could be true. The reference cited is a book by some Keane called Road of Bones.

“Thank the lord you have HE-SAW, WE-SAW, YOU-SAW under lock and key. I have never liked Burma or the Burmese and you people must have had a terrible time with them for the last fifty years… I wish you could put the whole bunch of them into a frying pan with a wall around it and let them stew in their own juice.”

The author writes about WWII being seen only from the European perspective, by which I suppose he means that the Japanese invasions of countries in Asia were never considered. However, he too writes about the Japanese invasions only in the context of the partitions of India, and not as part of the larger war. I think that a larger treatment of the Japanese invasions as part of WWII would have taken us farther away from the partitions of India which is what the book is supposed to be about. Having said that, we know that the biggest partitioning of India as India and Pakistan and our independence was rushed and hurried because Britain could not afford to fight WWII and manage the large empire at the same time.

This was after Lord Mountbatten was sent to India, first as head of the South East Asia Command, in 1943 and as Viceroy four years later. Sam Dalrymple’s treatment of the Mountbatten years is something of a caricature, with unnecessary details about their strange animal pets and his and Edwina’s personal lives, including his homosexuality. Even if true, none of this contributes to the reader’s understanding of the partitions of India or our independence movement.

In addition to the annexation of Burma being left out, the partition of the state of Bengal in 1905 is another glaring omission. This was, in fact, the first partition, and one that led to East and West Pakistan decades later. I must mention that Sam Dalrymple quotes liberally from Amartya Sen’s memoir, Home and The World whenever he needs to bolster his account of life in Burma or in Bengal, including the Bengal Famine, of course.

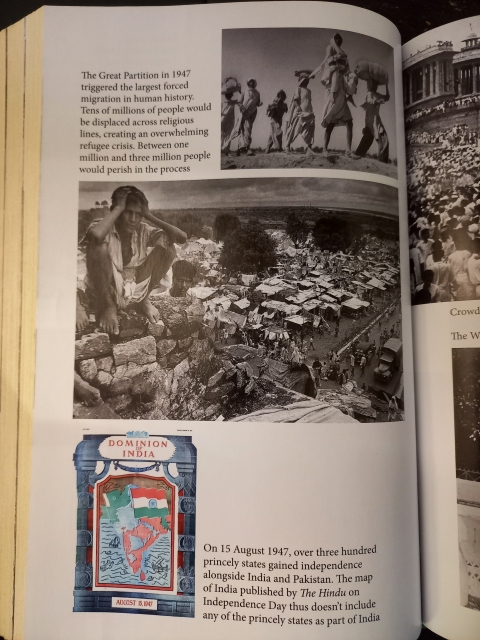

If the author spends too much time on Burma at the start of the book, he is also guilty of lavishing too much attention and time on the princely states of India. Three or more chapters are devoted to the accession by the various princely states to India at the time of India’s independence, notably Kashmir, Junagadh and Hyderabad. He justifies this by saying that two of them shared borders with Pakistan, while the third, Hyderabad, was the most wealthy and modern and was a predominantly Hindu state ruled by a remnant of the old Mughal Empire who also had plans to make Hyderabad the seat of the global Islamic Caliphate. In fact, he writes that the princely states were more important to deciding India-Pakistan partition than the Cyril Radcliffe Line.

In the chapter on Kashmir’s accession to India, Sam Dalrymple spends too much time on detailed incidents involving individuals and families that suffered at the hands of militias and lashkars, and too little on the deliberations that took place between the prince, Hari Singh, Sardar Patel and Nehru in the days that led up to India sending in the troops.

The author’s treatment of the divisions between Jinnah of the Indian Muslim League and the Indian National Congress too are absent and glossed over for the most part. These are critical to understanding the main partition between India and Pakistan that took place on religious grounds and they have their origins in the disagreements between the two parties and the creation of separate electorates by the British. From then on, it was a rift that continued to widen. In the chapter titled Dividing an Empire, Sam Dalrymple writes that Gandhi met the Mountbattens and suggested that Jinnah be made PM of India and that the cabinet be exclusively Muslim. This is preposterous and patently false, of course, and very irresponsible of a historian to even suggest this, knowing how incendiary something like this can be in India!

At the other extreme, the author also writes on more than one occasion in the book, about Sardar Patel maintaining close links with the militant Hindutva group, RSS, against Nehru’s wishes. He cites books by Six C and Jha as references, whoever they may be! I wonder if this doesn’t play into our current BJP-led Indian government’s narrative of a wide rift or chasm between Patel and Nehru – Narendra Modi’s refrain at many political rallies – which is quite unfounded to the best of my knowledge.

Shattered Lands also deviates from the main subject of India’s partitions to discussing pan-Arab nationalism that arose out of Egypt in the days of Gamel Abdel Nasser and how it spread across the gulf region eventually leading to the conflict between the NLF and FLOSY in the Yemen and southern Arabia region. This, and other diversions into student and labour movements across the West are quite unnecessary, as is the chapter Last Days of The Raj which has little to do with the partitioning of India, but problems in the Arab world.

India did get drawn into East Pakistan’s struggle for independence, however, and Sam Dalrymple deals with this subject in chapters titled Proxy Wars and Liberation. In fact, the other big surprise for me and something I was not aware of, is the insurgency and secessionist movements that were rising in India even as we attained freedom from British rule. I have read about proxy wars taking place in J&K, of course, with Pakistani support for insurgency and terrorist groups in POK, though the author does not deal with POK in any detail in this book. I am also aware of Naga insurgency getting support from across the Burmese border. But the fact that Naga and Mizo leaders were actively seeking support from East Pakistan, which is how the author describes it, and the extent of their close collaboration is news to me. Mizoram, particularly, strikes me as strange, because it is known to have a large Christian community who are highly anglicized in their ways; why they would seek help from Muslims in East Pakistan is curious to say the least.

The book even presents India’s involvement in Bangladesh’s war for independence from Pakistan, as primarily a way to put an end to East Pakistan’s support for these insurgency groups in the North-east. The author’s treatment of East Pakistan’s growing demand for a separate state begins with the language issue – between Bengali and Urdu – before it deals with Mujibur Rahman’s Six-Point Plan which included the separate state of Bangladesh. Sam Dalrymple writes of India’s involvement in helping East Pakistan secure independence, even as the US in its support of Pakistan during the Cold War years sent its USS Enterprise aircraft carrier to the Bay of Bengal. I don’t recall ever reading about this at the time of the Bangladesh War which lasted just 13 days!

In the epilogue to the book, the author writes about how the partitions play out in the subcontinent today and also of the Dastaan Project he undertook with his friends, of helping families separated by the partition find their loved ones and their old homes and old connections across the border between India and Pakistan. One can see, therefore, why he spends a lot of time on describing the travails of individuals and families affected by the partitions in the book. But I think he overdoes it, since many of these individuals and families don’t mean anything to readers since he also fails to make poignant, the connection between the individual human stories of the partition and the larger issues of nation states and independence from British rule that dominated at the time.

Finally, as a book of history Shattered Lands suffers from too many inaccuracies, false attributions, and obscure and recent references. It doesn’t just dwell unnecessarily on the Mountbattens’ personal lives and their infidelities, it even accuses our former Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, of having a relationship with her father’s secretary, MO Mathai, and cites Sagarika Ghose’s recent biography of Mrs Gandhi as reference! Then even as Mahatma Gandhi is falsely reported to have recommended Jinnah as Prime Minister with a Muslim Cabinet in the book, he is said to have disowned his eldest son for converting to Islam! I have read in Ram Guha’s book on Gandhi about his eldest son having come in for some very harsh treatment from his father, but I doubt it was over his becoming a Muslim! There is also mention of Mujibur Rahman becoming Prime Minister of Pakistan after the Awami League swept elections in East Pakistan, as if Pakistan and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto would have allowed it!

Needless to add, all of this strikes me as unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses’ mischief, whose meddling in book-writing and publishing knows no end! Not to mention their nonsense with book covers and design, as Shattered Lands’ ghastly green and pink cover with handprint shows. Not sure if the handprint is to suggest human, or to illustrate the five partitions!