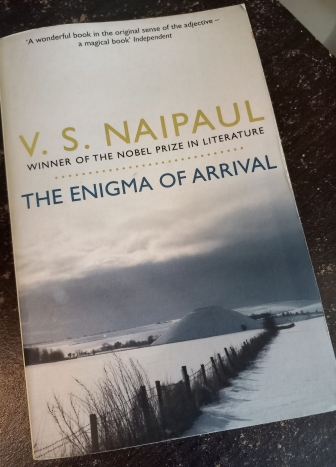

I was reading a book by VS Naipaul after a really long time, when my aged father presented me with The Enigma of Arrival for my birthday last month. I was looking forward to reading it, since I hadn’t read this particular book before. Of course, I had the nagging doubt that unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses would have meddled with this book as well. And as I shared on LinkedIn recently, I discovered early in the book that they had meddled indeed!

The book gets its title from a Giorgio de Chirico painting, The Enigma of Arrival, not familiar to me before. It depicts classical buildings around what might be a piazza, with two cloaked figures in conversation in the distance. Beyond them is a wall, hiding the sea from us, though the mast and sail of a large ship are visible against calm, blue skies. Naipaul thought it would be suitable for a new book he was writing, until he discovers that the story in his head is no more than a version of the story he is writing. He says that it was also “an attempt to find a story for, to give coherence to, a dream or nightmare” which for a year or so had been unsettling him.

It is in the second section of the book, called The Journey, that Naipaul writes about the painting and the title of the book. The Enigma of Arrival is a novel in five sections, and is said to be the most autobiographical of all his works. The book begins with the section, Jack’s Garden, which describes the author’s arrival in Wiltshire to stay at a cottage that belonged to a friend’s friend. It is mostly a description of his long walks in the area, all the way to Stonehenge almost, and back, and what he observes of the garden that Jack, the gardener is cultivating. The descriptions are written in the most dull and boring manner, and cannot possibly be Naipaul’s writing, as many of us who have read his books including those about his travels, know.

As if to enliven his descriptions or to show off his literary and artistic knowledge, the narrator (Naipaul) writes about the works of several artists, poets and writers, to tell us how much the countryside reminded him of several of these great works. For, as he says, this is an ancient part of Britain, and the land seemed to show it. From Constable’s painting of the Salisbury Cathedral, on landing at Salisbury, to comparing the shearing of sheep to something out of Hardy’s novels, the sight of geese reminding him of King Lear, autumn making him crave for Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and the sight of Amesbury reminding him of Guinevere, King Arthur and Camelot. Even Jack the gardener seemed Wordsworthian to Naipaul.

In a particular reference to life in the country, Naipaul says that the view that rural life is unchanging is “wrong”. This is the passage I shared on LinkedIn as it struck me as unprofessional PR agency mischief.

“Here was an unchanging world – so it would have seemed to a stranger. So, it seemed to me when I first became aware of the country life, the slow movement of time, the dead life, the private life, life lived in houses closed one to the other (sic).

But that idea of an unchanging life was wrong. Change was constant. People died; people grew old; people changed houses; houses came up for sale. That was one kind of change. My own presence in the valley, in the cottage of the manor, was an aspect of another kind of change… Everyone was ageing; everything was being renewed or discarded.”

This is clearly unprofessional PR agency mischief, guessing or knowing what I would write about cities being the harbinger of change in a recent blog post, in which I wrote that rural life is slow to change, it is where time seems to stand still. Of course, I wasn’t referring to the process of ageing or changing houses when I wrote my article!

Naipaul’s mention of Jack and the others owning motor cars, the farm manager owning a Land Rover and the sighting of a deer in the vicinity as well as segments of the ‘run’ also struck me as signs of unprofessional PR agency meddling!

There are no proper characters in this rather bucolic setting and one sensed early enough in the book that this is not a novel. The few characters that do make their appearance are rather shadowy and by this, I mean that they have no real role to play in the story except to provide a little texture to the background. They are all from the working class, gardeners and servants for the most part, another of unprofessional PR agency idiots’ obsessions. The book is full of what Naipaul himself refers to as Nature writing, Nature with a capital N. And sadly, writing of the worst kind that cannot possibly be Naipaul’s.

The second section, The Journey, is where Naipaul describes his journey from Port of Spain in Trinidad and Tobago to England to pursue higher studies and to become a writer. For no apparent reason other than PR agency idiot bosses’ mischief again, Naipaul takes a circuitous route to England via Puerto Rico and New York City, when Trinidad as a British colony would have surely had direct transportation links with UK. Naipaul also describes his journey back to Trinidad six years later and how it affected him.

“Six years before… Everything was tinged with the excitement of departure and the long journey to famous places, New York, Southampton, London, Oxford; everything was tinged with the promise and fantasies of the writing career and the metropolitan life. Now six years later the world I thought I had left behind was waiting for me. It had shrunk and I felt I had shrunk with it.”

England after this visit was like a second life to Naipaul. And he writes about projecting what he had read and experienced on to other lands.

“As a child in Trinidad I had projected everything I read on to the Trinidad landscape, the Trinidad countryside, the Port of Spain streets. (Even Dickens and London I incorporated into the streets of Port of Spain…

Now in Wiltshire in winter, a writer now rather than a reader, I worked the child’s fantasy the other way. I projected the solitude and emptiness and menace of my Africa on to the land around me.”

Naipaul also mentions three early books he wrote called Gala Night, Angela and Life in London, that I have never heard of.

In the third section, Ivy, a few more characters appear, but they are also mostly servants and gardeners. With no proper characters to take the story forward, and with several ideas or themes in his head, Naipaul seems to see every incident or person he meets as “material” for his writing. In describing people like Mr and Mrs Phillips, Bray, the car-hire man and Pitton, the only gardener left, the author also makes much of the fact that they are well-dressed and well-mannered as if they were townspeople although they were servants. He repeats this several times in the book.

It is as if he is comparing what he knows and understands of servants with what he experiences in Wiltshire. In fact, he does actually compare his own humble upbringing in Trinidad and his peasant life with those in Wiltshire and how vastly they differ. I think he overdoes this aspect and is quite unnecessary; not like Naipaul to feel ashamed of his background and of what he strangely keeps referring to as his “abstract” education and learning. He is usually not known to refer to himself as Hindu Asiatic-Indian or even Asiatic-Indian in his writings.

“As a child in Trinidad, I knew or saw few gardeners. In the country areas, where the Indian people mainly lived, there were nothing like gardens. Sugarcane covered the land. Sugarcane, the old slave-crop, was what the people still grew and lived by; it explained the presence on that island, after the abolition of slavery, of imported Asiatic peasantry…

There were gardens in Port of Spain, but only in the richer areas, where the building plots were bigger. It was in those gardens that as a child, on my way home from school in the afternoons, I might see a barefoot gardener… this barefoot gardener would be Indian. Indians were thought to have a special way with plants and the land.”

In the section Ivy, Naipaul also brings up the subject of decay, though he prefers to see it as change. However, I don’t understand how, in a landscape where he describes things in a state of “ruin” or “rotting”, he sees change and not decay.

“On this walk, as on the longer walk on the downs past Jack’s cottage, I lived not with the idea of decay – that idea I quickly shed – so much as with the idea of change. I lived with the idea of change, of flux, and learned, profoundly, not to grieve for it. I learned to dismiss this easy cause of so much human grief. Decay implied an ideal, a perfection in the past.”

I am not sure if ivy works as a metaphor for decay or death, because Naipaul mentions that trees on the grounds of the manor were being killed by ivy, several times in this section. In the next section, Rooks, we do have death. Pitton the gardener has been let go, and people die: Alan, the literary man as well as Mr Phillips pass away. There’s also a new, unnamed neighbour who used to be from these parts of Wiltshire and recalls his past in these surroundings.

Amid the squawking of the rooks, as they look for places to build their nests, elms start to die as well. And with this, the countryside is being turned into flat and open land.

There is still more death to come in the last section, The Ceremony of Farewell, where Naipaul’s own sister, Sati, dies and he travels to Trinidad for her funeral ceremony, as does his brother, Shiva Naipaul.

The Enigma of Arrival – at least this PR agency idiot bosses’ version – is disjointed and is certainly not a novel. It reeks of unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses’ meddling and mischief and it is unfortunate that I am having to read and write about a book that was not written by VS Naipaul in all probability. It says nothing about life in Wiltshire, or in the Caribbean, nor is it about Naipaul’s journey to England.

Neither arrival nor departure, this Enigma of Arrival will remain a mystery!

The featured image at the start of the post has been created by the author in Canva (not using AI, I must clarify), from images of a map of Trinidad and Tobago courtesy CIA, and an aquatint of Oxford University where Naipaul studied courtesy JW Eddy on Wikimedia Commons