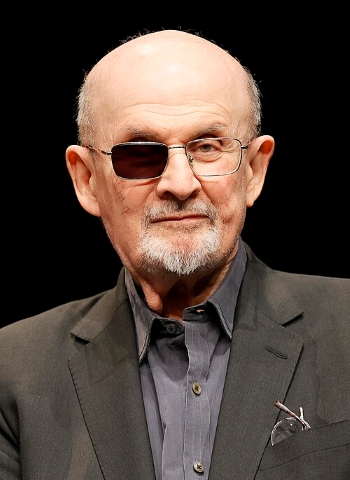

Last month, I finished reading Salman Rushdie’s Knife, the book he wrote about the attack on his life in the US, having survived it. This book was sent through my younger sister, Bhavani, last year ostensibly for my aged father to read. Unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses have been meddling for decades now, with and through my sister. Anyway, after the awful edition of War and Peace that I read and have written about, I wished to read something that was not a novel.

I don’t know of any book about an assassination attempt on a writer, who lived to tell the tale. So, in this sense, it is already a very unusual subject to be writing about and still more strange to be reading. Rushdie does write about Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz who was attacked in Cairo in 1994, but I don’t think he wrote about the attack ever. Apparently, Mahfouz was attacked for opposing the fatwa against Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, and even though he lived for another twelve years, the injuries he sustained permitted him to write for only a few minutes each day.

Knife is divided into two parts, The Angel of Death and The Angel of Life, with four chapters in each section. The first thing that struck me as a reader was the sense of detachment with which it is written. Remarkable for someone whose life was threatened with a nearly fatal attack just a year or two before his recounting of it. But then, as he writes, he’s already lived through so many years of living under the same constant threat, that this was another – more physical – blow to his life. He doesn’t wallow in self-pity or any of the “Why me?” nonsense. Instead, he deals with it head-on, as courageous writers are meant to do.

Rushdie opens the book with a little bit about the Chautauqua Institution in upstate New York where he was invited to speak and where the attack took place. He writes about it being a place of refuge for writers facing danger or persecution in their own countries.

“I was with Henry Reese, co-creator, along with his wife, Diane Samuels, of the City of Asylum Pittsburgh project, which offers refuge to a number of writers whose safety is at risk in their own countries. This was the story Reese and I were at Chautauqua to tell: the creation in America of safe spaces for writers from elsewhere, and my involvement in that project’s beginnings. It was scheduled as part of a week of events at the Chautauqua Institution titled: More Than Shelter: Redefining the American Home.”

The irony couldn’t be more telling. A knife attack on a writer who is there to speak about creating safe spaces for writers. The first chapter also titled Knife is part reminiscing about Chautauqua on the eve of his speech with enough to suggest what is to follow – which he calls the literary device of foreshadowing – and part description of the attack with enough details for the reader to know what 15 stabbings are capable of. It ends with him being flown on a helicopter to the nearest hospital with a trauma centre.

The matter-of-fact manner in which much of this is described is because Rushdie says, it felt matter-of-fact. The fact that he was dying.

“’No tunnel of light.’ No feeling of rising out of my body. In fact, I have rarely felt so strongly connected to my body… It was an intensely physical sensation. Later when I was out of danger, I would ask myself, who or what did I think the ‘me’ was, the self that was in the body but was not the body, the thing that the philosopher Gilbert Ryle once called ‘the ghost in the machine.’ I have never believed in the immortality of the soul and my experience at Chautauqua seemed to confirm that.”

I think some of the matter-of-fact description also comes from the fact that Rushdie preferred to place his life in various doctors’ and therapists’ hands with complete confidence. He refers to his many doctors as Dr. Hand, Dr Eye, Dr Liver, and so on, and you get the sense that there were an army of doctors working on various parts of him for several weeks and months. He does say that the one thing he did feel, and that crossed his mind, was the loneliness of it all, of dying far away from family and friends.

Well, he didn’t have to worry very much on that count. Much of the book and his recovery in hospitals is about how much strength and support having his family around gave him. Most of all his wife, Eliza Griffiths, to whom he has dedicated an entire chapter. His gratitude and love for her comes shining through brilliantly throughout the book. He also draws strength from his family – his sons, Zafar and Milan and their families as well as his sister, Sameen, and her family. The sense of family and the protection and love it offers is brought out really well in the book, including the fact that family lived on more than one continent. The passage about his son, Milan’s fear of flying, and having to take a ship, Queen Mary 2, from UK to be with him is particularly poignant.

Rushdie also takes comfort and solace in recalling the writings of other authors, many of whom also happen to be his friends. Knife is generously sprinkled with the thoughts and recollections of many writers. I think this perhaps helped him deal with his own situation better and it also helps him connect with readers. Rushdie himself writes about his free-associative mind and way of thinking. From recalling the French writer Henry de Montherlant (who, I must admit I had never heard of) who said “Happiness writes in white ink on white pages” and realizing that writing about happiness is extremely challenging, to writing about the optimism of Voltaire’s Candide and the gumption that Robert M Pirsig writes about in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, to plenty more, these are thoughts that occupy Rushdie’s mind when he’s not bothered by his wounded eye, his injured hand and all the several stitches and staples across his body.

Rushdie is also acutely aware of the fragility of life, even as the voice in his head keeps saying, “Live, live.” Remember, much of the events described in Knife took place during the Covid pandemic years. And even as he writes about other writers and their work in various contexts, he is also friends with some of them who suffer terrible attacks and sadly die in the meantime. His thoughts go to Hanif Kureshi who suffers a stroke kind of attack while in Rome with his wife. Then he writes about Milan Kundera passing on, as well as Martin Amis.

In the second section of the book which deals with him leaving the various hospitals and trying to slowly get back to a normal life at home with Eliza, an entire chapter is dedicated to a conversation with the would-be assassin. Rushdie doesn’t once refer to Hadi Matar by his name in the entire book, but decides to call him A. like Kafka’s K., I suppose. He contemplates meeting with A. at various times during his treatment and recovery, but Eliza Griffiths firmly disallows it. There is a paragraph in the very first chapter which tells us, rather alliteratively, how he decides on A. as a name for his attacker.

“I do not want to use his name in this account. My Assailant, my would-be Assassin, the Asinine man who made Assumptions about me, and with whom I had a near-lethal Assignation… I have found myself thinking of him perhaps forgivably as an Ass. However, for the purposes of this text, I will refer to him more decorously as the ‘A.’”

Rushdie decides to engage in an imaginary meeting and conversation with A. This is the subject of an entire chapter, and the conversations take place in four sessions. While it is an interesting creative device, the conversations are quite laboured and contrived. And having all of them bunched together in one chapter doesn’t do justice to his need for a meeting with his assassin, and for seeking some kind of closure, as he says. All that the imagined conversations with A. manage to do is to tell us that A. hadn’t read enough of Rushdie’s books to know what he was about, and that A. remains unrepentant throughout and that A. wouldn’t have a life while Rushdie would go on to live his life as before. There is also an Imam Yutubi who A. keeps referring to as his spiritual instructor! And there is mention of Malcom X and Frantz Fanon in the conversation as well. Some of you might have read my posts on LinkedIn, about the Frantz Fanon book that was planted in my luggage by unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses, along with a picture postcard of my aged father in a casino called Money Tree in Las Vegas, Nevada, but I am sharing links to these posts anyway.

All this strikes me as the mischief of unprofessional PR agency idiots meddling in book writing, editing, publishing etc. yet again. In fact, the imagined conversations happening in their heads probably comes from guessing a WhatsApp chat between me and an old college friend, about Arundhati Roy’s book, Ministry of Utmost Happiness years ago. One of my many disappointments with the book was that it hardly had any conversations or dialogues in it, for a novel. My friend was of the view that the conversations were happening in the characters’ heads, a view that I do not share.

Just like the same unprofessional PR agency idiots had meddled with Amartya Sen’s Development as Freedom book that I bought and read years ago, some of which also came from guessing ex-Ogilvy WhatsApp conversations! This nonsense has reached such ridiculous levels that I now think they have hacked into WhatsApp as they have done with all our emails.

Rushdie’s description of Hadi Matar as a 24-year-old man dressed in black who stabbed him 15 times seems the work of unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses in India, who have been desperately trying to make me Sarada, my former junior colleague at Ogilvy Delhi. They are quite capable of having engineered the attack itself, and I wouldn’t put it past them.

The other thing that keeps him and his wife, Eliza, going is his new book, Victory City, which I haven’t read, that he finishes proof-checking just before the attack. His wife, Eliza, too has her new novel Promise released as they return home to restart their lives.

Knife is well-written for the most part and quite readable. Would I buy it to read about the attack on Rushdie’s life? Probably not.

Postscript: I happened to see a strange video of an interview with Salman Rushdie and his wife, Eliza, by CBS news online. It was pushed into my Google search. You may watch it, if you like.