What a relief it was to have finished reading the epic war novel War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy! I was so happy to close the third volume shut that I shared a post on LinkedIn about how relieved I was. It took up my early morning hours – for that is when I do my reading – for soooo many months, that I was tiring of reading it. But I persisted, and was determined to finish reading it, so I could write about it and share my observations on the book with all of you.

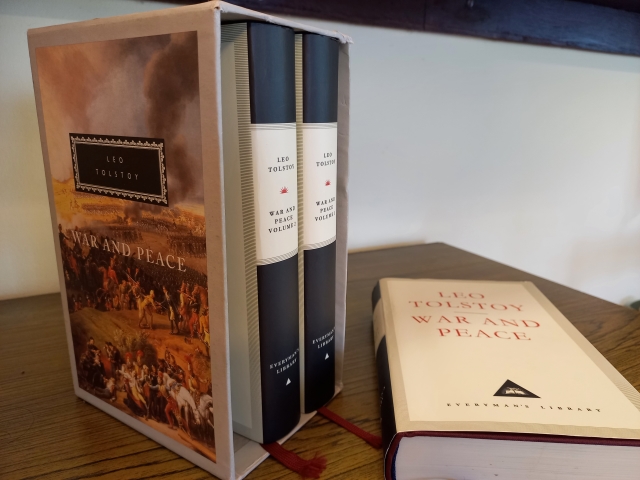

My aged father in Goa gave this book to me on my birthday last year and on just leafing through it at the time, I could tell it was full of unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses’ meddling in publishing yet again. I think I shared my initial observations regarding this Everyman’s Library edition from Alfred Knopf then itself on LinkedIn and X. Now that I have finished reading all three volumes of it, I can say without a doubt that it is replete with their mischief and meddling.

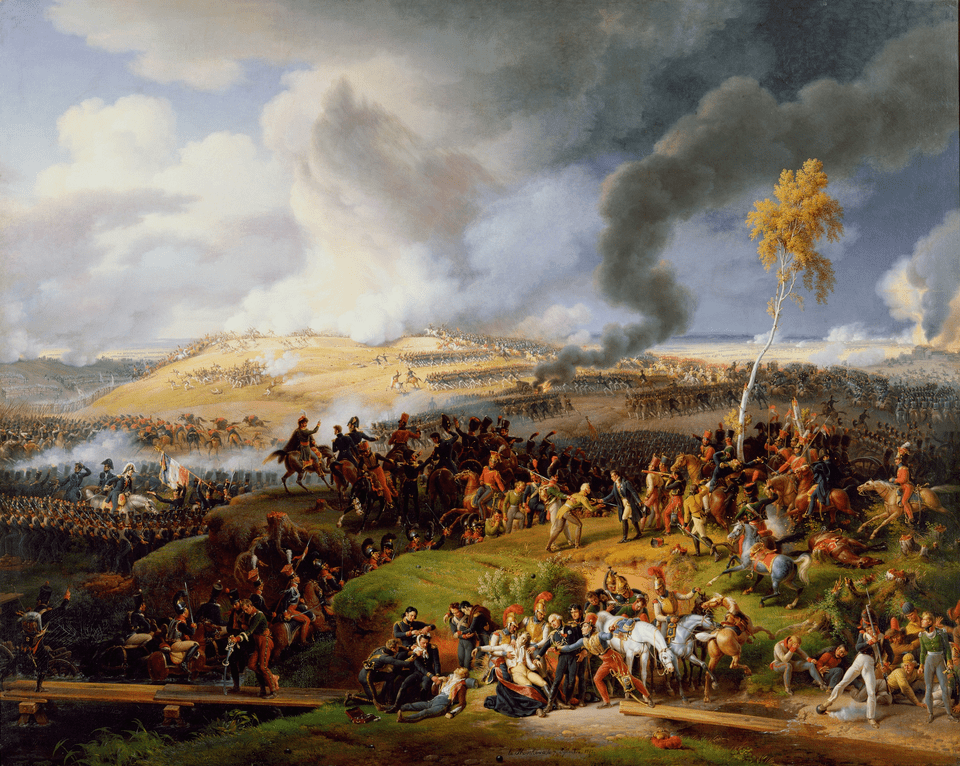

For a book that is supposed to be about the Napoleonic Wars, and set in the times when Napoleon Bonaparte attacked Russia and even entered Moscow and took it over in 1812, it is quite lacking in serious historical context and also in the drama of war. In an introduction to the book by RF Christian – haven’t we read some strange introductions in books, ever since PR agency idiot bosses started meddling in book-writing and publishing decades ago – he writes that Tolstoy’s description of the war and combat scenes are beyond compare, but he tells us little that even sets the novel in context. In fact, Tolstoy’s detailed and fantastic descriptions of the war scenes help to prove my point – that the book dwells on details but fails to provide the larger picture which is the context.

This is not a problem with the book not providing historical chronology; in fact, there is a detailed list of principal historical events with years/dates before the novel even begins. Yet, the events, characters and the situations that develop as the story progresses have little to do with the larger historical context. I found this especially strange since the principal characters are all from aristocratic families – counts, countesses, princes and princesses as well as military commanders – who seem to be so divorced from the immediate reality of war and conflict. So, we have the detailed battle scenes described in graphic detail, but these have no connection with the characters or the war, even as it is being waged. It is as if the battle scenes and attacks are taking place in, and for themselves, with no bearing or relation to the war that France is waging on Russia. Tolstoy himself was a Count and came from an aristocratic family, so he would have been quite familiar with their lives and their political influence.

War and Peace was always on my must-read list until now, as I always thought of it as an epic war novel. It is a work of fiction set in wartime, though Tolstoy insists it is not a novel in the epilogue, and more about this later. However, the characters flit in and out, as if on stage but without any of the drama. The story never really gathers depth and momentum, nor intrigue and drama. The main dramatis personae are the elite of Moscow and St Petersburg – aristocrats as I said earlier – who remain relatively untouched by the war.

Instead, most of the pages of this 1500-2000-page novel are about the aristocrats’ social soirees, balls and dinner parties and salons. In the second chapter of the first volume of War and Peace, the first such soiree is taking place and Tolstoy likens the hostess, Anna Pavlovna, to a spinning mill foreman:

“… she resumed her duties as a hostess and continued to listen and watch, ready to help at any point where the conversation might flag. As the foreman of a spinning mill when he has set the hands to work, goes round and notices, here a spindle that has stopped or there one that creaks or makes more noise than it should, and hastens to check the machine or set it in proper motion, so Anna Pavlovna moved about her drawing room , approaching now a silent, now a too noisy group , and by a word or slight rearrangement kept the conversational machine in steady, proper and regular motion.”

I have no idea about spinning or about mills, but this strikes me as unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses’ mischief and meddling. I could see early on in the book why they were interested in aristocrats and soirees so much, given their obsession with hijacking my work on Passport Scotch Whisky during my years in Ogilvy Delhi and indeed all of my career in the advertising and brand communications industry in India. This is why they have chosen to meddle most in these sections, especially with the ladies and their looks as well as clothes. What struck me as strange is that in Russian high society of the early 19th century, it is the women protagonists who hold soirees and conduct salons, not their male counterparts. However, this also provides unprofessional PR agency scoundrels plenty of opportunities to do mischief, with the women characters in War and Peace. From detailed descriptions of the women getting dressed for the balls in which maids express dissatisfaction with their ladies’ outfits and hairdos and the ladies go through costume changes, to women being described only for their beauty even though “men thought her intelligent, for she hosted the most attended salons”, and the like. You get the drift, I hope.

“It was not the dress, but the face and the whole figure of Princess Mary that was not pretty… but they still thought that if a blue ribbon were placed in the hair, the hair combed up, and the blue scarf arranged best on the maroon dress, and so on, all would be well.

‘…No, Mary, really this dress does not suit you. I prefer you in your every day grey dress. Now please, do it for my sake. Katie’, she said to the maid, ‘bring the princess her grey dress and you’ll see.

‘… At least change your coiffure,’ said the little princess. ‘Didn’t I tell you?,’ she went on… ‘Mary’s is a face which such a coiffure does not suit in the least. Please change it.’”

Related to this problem of lacking context, War and Peace has sections which deal with the war separately. I don’t mean only in separate chapters, but in a way that is divorced from the characters’ social interactions and lives. It is as if the war is taking place somewhere far and unconnected, and the characters have little to do with it even though they might occasionally discuss it over dinner and even though two of the male characters in the book, Prince Andrew Bolkonsky and Nicholas Rostov, actually join the Russian troops and fight the war against Napoleon Bonaparte. There is hardly any reference to these men who are away fighting in the war: their family members don’t think about them, there’s little to no correspondence with them.

Rarely do the social interactions and lives of the characters and their war participation meet or cross each other. Or perhaps they do, only in the eyes and the experience of Count Pierre Bezukhov, an illegitimate son of an old Count Bezukhov who legitimizes Pierre as his son and leaves all his wealth and estates to him before he dies. Pierre in this sense is an outsider who becomes an aristocrat overnight, yet yearns for a life of action and bravery and wishes to join the war. He becomes a Free Mason instead thinking that it might provide him with a path to greatness, and yet in a strange twist that is quite Kafkaesque, is taken prisoner by the French troops while trying to save a young girl when Moscow was burning.

I am not sure this neat compartmentalization of War and Peace into two parallel sections was intentional on the part of Tolstoy; far from helping him communicate a story or message, it takes away from the main purpose of the novel whatever it might have been. In fact, I am not sure what War and Peace is actually about. The futility of war, the aristocrats’ lack of involvement in it despite being great patriots, a love story set against the backdrop of war… what?!

In between these neat compartments corresponding to war and peace, there are several chapters in which Tolstoy shares his thoughts with us on the war. Not on this particular war alone, but on wars in general, why they are fought, how the will of great kings and emperors are not necessarily carried out by their generals, why certain events took place such as Moscow’s abandonment, Austria turning from ally to foe, even a brief rapprochement between Russia and France which later fell apart, the burning of Moscow and parts of Russia when the French troops had entered Russian territory, etc. In some of these explanations, the author writes about the historians’ views, how real power is exercised, the will of the masses of people, etc.

The sections of the book that deal with the war also lack drama and intrigue. Even as war plans are being discussed, bridges are being blown up, troops’ movements are changed, and other such situations, one senses no tension, no intrigue or fear. Disagreements of some of the military commanders such as Kutuzov to adhere to the plan which is what is said to have contributed to Russia’s abandonment of Moscow, is also dealt with in the most placid and matter-of-fact manner, when it could have been a great opportunity to build Kutuzov’s character.

Let me spend some time discussing the characters in War and Peace and what Tolstoy might have intended to communicate through them. There are three main aristocratic families, the Bolkonskys, the Rostovs and the Kuragins, the last of whom tries to attach itself to the former two who were perhaps wealthier or better connected, through marriage. There are no stand-out characters through whom Tolstoy is trying to tell us something important. The men are all busy with their estates and while supporting the war effort and occasionally talking about it as patriots are actually quite distant from all of it. Except when the war comes too close to them and the French troops are in the vicinity and coming for their estates and homes. I don’t know if having the characters speak in French every now and then was part of Tolstoy’s original novel, and whether he intended to convey the aristocrats’ hypocrisy and pretentiousness through this device, but the book is full of it. I believe it was the fashion among high society folk in Russian capitals of those years to speak French, as the introduction to the book tells us.

Anyway, as it turns out, Prince Andrew Bolkonsky who joins the Russian war effort actually secretly admires Napoleon Bonaparte. It doesn’t interfere with his war duties, but it certainly tells us that Russian aristocrats didn’t think twice about admiring a warrior king such as Napoleon, a small failing perhaps. In the end the Russians prevailed and drove the French out of Moscow, but that is another story, also one Tolstoy doesn’t tell in War and Peace. Andrew Bolkonsky loses his wife, Elizabeth, soon after their son is born who is left in his sister, Mary’s, care for the rest of the book. Yet he falls in love with Natasha but is expected to put off their wedding by a year and so he does, losing her as well. He comes across as a rather weak character overall.

Nicholas Rostov, on the other hand, also the son of an old Count Rostov, and Natasha’s brother, joins the Russian army to fight against Napoleon’s forces. He is a typical soldier, conscientious in his work and always aware of his responsibilities, even when he runs up large debts and has to repay them. He has no great illusions or ambitions and is content to follow orders and do his duty. Again, Tolstoy does not create a character out of Rostov to help him tell his story. And Pierre Bezhukov, I just described a short while ago.

The women characters are even more pathetic, some of them caricatures even. While it is admirable that they hosted balls and salons, and also exerted their influence in the corridors of power and made marriage matches between eligible and wealthy family members, their part in keeping the household together during wartime and in managing estate matters is negligible. I think there were opportunities to build the women’s characters as strong-willed women who were preservers of family life at a time of war, with the old patriarchs in failing health and the young men away at war or managing the estates, but that is not what we have here. The women in War and Peace are almost all aristocrat ladies who play their part as society ladies, hostesses of salons and balls and exerting what little influence they have. The two main women characters, Mary Bolkonsky and Natasha Rostov are a study in contrasts. Mary – Prince Andrew’s sister – decides not to marry early on in her life and to look after her aged father, and to this extent her character is consistent with her wishes as the sensible, mature woman. Natasha is a young, vain and capricious girl, full of life and energy but not knowing how to channel it. She is the object of many men’s attention, and is meant to marry Andrew but they put off their engagement by a year, during which time she falls for the charms of Pierre Bezhukov and had already had a romance with Denisov, one of her brother’s – Nicholas Rostov’s – friends.

Then, there is Helene, the one of unparalleled beauty from the Kuragin family who marries Pierre Bezhukov. She is the woman who men think is intelligent because she hosts several salons, though her husband Pierre himself doesn’t think much of her. Tolstoy refers to Pierre as the Gentleman of the Bedroom Chamber soon after he becomes Count Bezukhov.

“To be received in Countess Bezukhova’s salon was regarded as a diploma of intellect. Young men read books before attending Helene’s evenings, to have something to say in her salon, and secretaries of the embassy and even ambassadors, confided diplomatic secrets to her, so that in a way, Helene was a power. Pierre who knew she was stupid sometimes attended with a strange feeling of perplexity and fear, her evenings and dinner parties, where politics, poetry and philosophy were discussed.”

They part ways when Pierre joins the Freemasons and she marries someone else, but after a year or more, they rejoin in matrimony and are together until she dies. It is when Helene is contemplating divorce from her second husband that Tolstoy introduces two men – a magnate and a prince who have rights over her! I was so aghast at reading this, that I shared it in a post on LinkedIn. It reeks of unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses and their attitude towards women.

“In Petersburg she had enjoyed the special protection of a grandee who occupied one of the highest posts in the Empire. In Vilna, she had formed an intimacy with a young foreign prince. When she returned to Petersburg, both the magnate and the prince were there, and both claimed their rights. Helene was faced by a new problem – how to preserve her intimacy with both without offending either.”

And finally, how can I leave out Sonya, who is part of the Rostov family but also not part of it. Sonya’s position in the family is never made clear, except that she and Natasha are close friends, and she is always referred to as the poor one, the plain Jane. Through most of the book, the author tells us that Nicholas Rostov is in love with Sonya and that sometime in their growing up years, Nicholas even promised to marry her. Elsewhere in the book she is described as a poor cousin!

There is so much of this kind of nonsense that I cannot imagine Tolstoy wrote, which is why it is perhaps not fair for me to write a review as such, but I thought I must share the kind of mischievous meddling that unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses engage in as well as the extent of it.

The book ends with two epilogues, as if one wouldn’t be enough. Not just that, the epilogues are long, written in chapters. The first epilogue deals with the later lives of the families and the main characters, which again have little to do with the war. The second epilogue is where Tolstoy tries to explain why he wrote War and Peace. It is here that he declares, rather ridiculously, that the book is not a novel! I think the whole world knows War and Peace to be a historical novel, decades before it even became a genre of literature. He also uses a strange analogy with the laws of motion in physics to explain how historical events are generated by the force of momentum. At the end of the book, in an appendix published in Russian Archive, 1868, Tolstoy offers an explanation for why he leaves the serfs out of War and Peace and concentrates only on the aristocratic families: because too many horrors of the lives of serfs have already been depicted.

“When the first part of this book appeared some readers told me that this (the character of the period) is not sufficiently defined in my work. I reply that I know what the characteristics of the period are that people do not find in my novel – the horrors of serfdom, the immuring of wives, the flogging of grown-up sons… but I do not think that these characteristics of the period as they exist in our imagination are correct, and I did not wish to reproduce them… That period had its own characteristics (as every epoch has), which resulted from the predominant alienation of the upper class from other classes, from the religious philosophy of the time, from peculiarities of education, from the habit of using French language and so forth. That is the character I tried to depict as well as I could.”

This is what struck me as most odd about War and Peace. Not only is it about aristocratic families in Russia who have little to do with the war against Napoleon, it completely leaves out ordinary Russian folk and what they made of the war. If Tolstoy believes that wars are fought and are won or lost based on the will of the people as he explains in some of the chapters, he ought to have focused more on the part that ordinary Russians played in the war as also their lives. After all, Tolstoy was a Count who is best known for giving up his estates and wealth in the service of the poor and for the emancipation of serfs. Yet, ordinary people are missing in this telling of the Everyman’s Library edition of War and Peace.

And I ought to conclude this piece with what I think is the main reason for unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses’ meddling with this book – their primitive and stupid preoccupation with the farming vs hunting narrative of human civilisation. There is an elaborate hunting scene in a forest with the aristocrats preferring to indulge in their version of war – for game.