After reading all three volumes of Mahatma Gandhi’s Moral and Political Writings edited by Raghavan Iyer, which belong to my aged father and about which I wrote a blog post not too long ago, I thought it’s time to read about his thoughts on Hinduism and women.

The two slim books, What Is Hinduism? and Gandhi and Women, are also part of my aged father’s library at home in Goa. The first is a collection of extracts of Gandhi’s writings in publications such as Harijan, Navjivan and Young India, on various aspects of Hinduism, published by National Book Trust on the occasion of Gandhi’s 125th birth anniversary in 1994. According to the Chairman of the Indian Council of Historical Research, Mr. Ravinder Kumar, who writes a preface to this compilation, “… even though these contributions were written on different occasions, they present a picture of Hindu Dharma which is difficult to surpass in its richness, its comprehensiveness and its sensitivity to the existential dilemmas of human existence.”

These articles – or excerpts/extracts of articles – are meant to explain what Hinduism stands for, how it fits with Gandhi’s own views of non-violence, the caste system, equality of religions, communalism and more. First, Hinduism itself is explained in terms of what it meant to Gandhi and how he experienced it. In his view, Hinduism is not so much a religion as a way of life. He quotes from the Vedas and the Upanishads to corroborate his belief that Hinduism is a path to seeking oneness or communion with God.

In Gandhi’s view, the striving for oneness with God is the search for truth, and hence inherent in this quest for truth is the spirit of non-violence. He also believes that Hinduism in its purest sense – not as practised in his time or now – is most tolerant of all other religions and beliefs. He also uses the fact that one is Hindu only by birth and that there is no proselytizing in Hinduism, to argue that it is a growth of ages and therefore at peace with all religions.

Gandhi explains why he considers himself a Sanatani Hindu in a chapter titled Hinduism from Young India October 6, 1921, and offers four reasons for it.

“I call myself a Sanatani Hindu because,

- I believe in the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Puranas, and all that goes by the name of Hindu scriptures and therefore in avataras and rebirth;

- I believe in the varnashrama dharma in a sense, in my opinion, strictly Vedic but not in its present popular and crude sense;

- I believe in the protection of the cow in its much larger sense than the popular;

- I do not disbelieve in idol-worship.”

Not familiar with the Sanatana Hindu concept, I was quite puzzled by the recent political controversy that erupted in India. From the news reporting of it, it seemed to be centred around the caste system that Hinduism follows. I suppose Gandhi too means sanatana in the same sense, since he believed in the varna system, though he thought the caste system with its practice of untouchability abominable.

In the very next chapter in the book, titled Sanatana Hindu, he writes in defense of his interpretation of Hinduism saying he is not a literalist, but tries to understand the spirit of the various scriptures of the world. He rejects the story of a Shudra being punished by Rama for daring to learn the Vedas. He also delineates the Rama of the epic by Tulsidas from the Rama of history and maintains that it is the spiritual experience of the Ramayana that holds him spellbound.

For some strange reason, several chapters in the book are his speeches to groups of people in Kerala and southern India. Haripad speech in Travancore, Kottayam speech, Quilon, and Krishna Janmashtami speech in Mysore state.

In other chapters, Gandhi addresses issues regarding Hinduism and religion more generally that are not in the spiritual realm but appeal to reason and the intellect. For example, the issue of Yajna or sacrifice, brahman vs non-brahman, untouchability, equality of all religions and such like that make us think about the principle behind some of these well-entrenched beliefs and even question them. He writes quite extensively on what the Gita means to him and even answers questions or doubts about whether the spirit of Krishna’s advice to Arjun as his charioteer was compatible with the principle of non-violence of Hinduism.

The second book that I just finished reading is titled Gandhi and Women and is written by Madhu Kishwar, a well-known women’s rights activist and feminist in India. She analyses Gandhi’s attitudes and beliefs towards women, both based on his writings as well as in actual practice during the long struggle for India’s freedom. A slim volume of even fewer pages than the book on Hinduism, it is a work of astute observation, research and analysis. And when you consider that of all of Gandhi’s many contradictions, his attitude towards women was perhaps the most contradictory and even contrarian, it takes a fine mind to parse his thoughts, actions and writings and present the findings to us in a balanced and nuanced way.

Throughout Gandhi’s interactions and his writings on women and issues concerning them, two broad themes emerge from this book. He was all for women’s emancipation, because he could see the strength of women’s power when mobilized in large numbers. And he didn’t stop appealing to women to join India’s freedom movement; instead, he rallied them in their hundreds and thousands whether it was the boycott of foreign goods, the spinning and popularising of khadi, as well as the Salt March. According to Madhu Kishwar, “it was with remarkable insight that Gandhi, without challenging their traditional role in society, could make women an important social base for the movement. As with the other important groups such as students and the peasantry, he told them they had to take the responsibility not just for changing their own economic situation, but that of society at large.”

She quotes Gandhi as saying, “I swear by this form of Swadeshi, because through it, I can provide work to the semi-starved, semi-employed women of India. My idea is to get these women to spin yarn, and to clothe the people of India with khadi woven out of it.” Kishwar says the response was overwhelming: over one hundred thousand women opted for the programme, as opposed to less than 10,000 men. Similarly, she writes that the Salt Satyagraha “once again proved Gandhi’s genius for seizing the significance of the seemingly trivial but essential details of daily living which are relegated to the woman’s sphere. Salt is one of the cheapest commodities which every woman buys and uses as a matter of routine, almost without thought.”

In terms of social reform too that India badly needed at the time, Gandhi was a huge champion of women’s rights. He believed that child marriage had to be ended, women ought to have the right to say no, young widows should be allowed to remarry, dowry and the practice of sati must be abolished, and the like. However – and this is where the second broad theme of Gandhi’s views come into play – he was of the view that women ought to rise and exercise their rights for greater social good. That women were inherently non-violent, and that their best expression of themselves is always in a larger social context.

If we find it somewhat limiting, this is exactly what Gandhi intended. He was of the view that women should not compete with men, rather they should support and help them in their endeavours. Gandhi also believed that the woman’s sphere was home and family and this is where she should focus all her energies, leaving breadwinning work to the man. Gandhi is said to have written,

‘She is passive, he is active. She is essentially mistress of the house. He is the bread-winner, he is the keeper and distributor of the bread.”

Kishwar goes on to say that this active-passive syndrome has been an ideological device for denying women any chance to acquire power and decision-making ability in the family and in society. That the unjust domination of women that Gandhi opposed was, in fact, being helped by this separation of spheres or division of labour.

Given these beliefs of Gandhi’s, what is surprising is how he managed to enlist the cooperation and support of so many highly accomplished women leaders of the time in his fight for independence. Sarojini Naidu, Annie Besant, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Sucheta Kripalani, Vijayalakshmi Pandit and so many others were no stand-ins for anyone, nor were they housewives. Kishwar writes that “he is one of those few leaders whose practice at times moved in directions other than those suggested by his theories and his stated ideas. Just as in his early years, he kept insisting he was a loyal citizen of the British Empire even while objectively cutting at the roots of British imperialism, so also he could keep on harping on woman’s real sphere of activity being the home, even while actively creating the conditions which could help her break the shackles of domesticity.”

The most puzzling and even controversial views of Mahatma Gandhi regarding women are to do with his experiments with celibacy or sexual abstinence and restraint. They were an integral part of his life at the Ashram he had created, as well as his experiments with truth. He even went to the extent of conducting his brahmacharya experiments with his own relation, Manu, who was only 19 years old. The extremes to which he took his beliefs on sexual restraint are difficult for most people to comprehend, but not if you consider his views on marriage and sex. Sex was considered important only from the procreation perspective and otherwise something to be avoided. Besides, according to Madhu Kishwar, Gandhi actually “didn’t consider marriage and motherhood as the only mission in life for every young woman… to choose to remain unmarried for the nobler purpose of serving society was a much more preferable ideal for self-realisation.”

Kishwar writes that Gandhi believed that women ought to have the right to say no and refuse sex to their own husbands. I wonder what he would have to say about our laws even in the 21st century where marital rape is not considered rape. Further, she writes that if women were to assert themselves in family life “wives should not be dolls and objects of indulgence, but should be treated as honoured comrades in common service.” She writes that Gandhi was also of the view that women must protest against being treated as sex objects; Gandhi is believed to have said “…If you want to play your part in the world’s affairs, you must refuse to deck yourselves for pleasing man” and revolt against “any pretension on the part of man that woman is born to be his plaything.”

Some of these statements of Gandhi’s have strange attributions in the reference notes, for example, cited in “To the Women”. It appears that this book was originally published as a set of two articles in The Economic and Political Weekly in 1985 before being published by Kishwar’s own Manushi Prakashan. I have no way of contesting or verifying these attributions, of course, but suffice it to say that they do raise suspicions of unprofessional PR agency idiot bosses meddling in this book, even if it does belong to my aged father. They have interfered with his books right under our noses, as well as so many of mine while in storage at the packers and movers’ warehouse in Chennai two decades ago and also in transit, as I have been writing on my blog and in social media. Another of these strange and suspicious inclusions is Sarla Devi Chaudhrani, who is mentioned in Kishwar’s book as well, besides Ram Guha’s book on Mahatma Gandhi, Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World, which I reviewed on my blog long ago.

That said, for many of these seemingly forward-looking and progressive views on women especially for the times Gandhi lived in, he still remained wedded to the idea of Sita as the ideal woman or wife. Kishwar writes that he was not so enamoured by Rani of Jhansi as he was by Sita. I suppose this tells us that Gandhi’s idea of the emancipated woman was more about liberating her moral and social force, than her individual economic force which would make her compete with men.

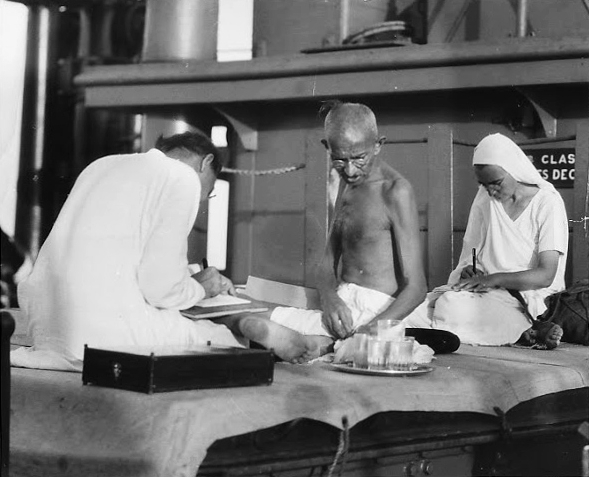

The featured image at the start of the post is of Mahatma Gandhi at work during his voyage to England and is from Wikimedia Commons. With him is Madeleine Slade, also called Mirabehn.